Čapek’s Hordubal in Plural

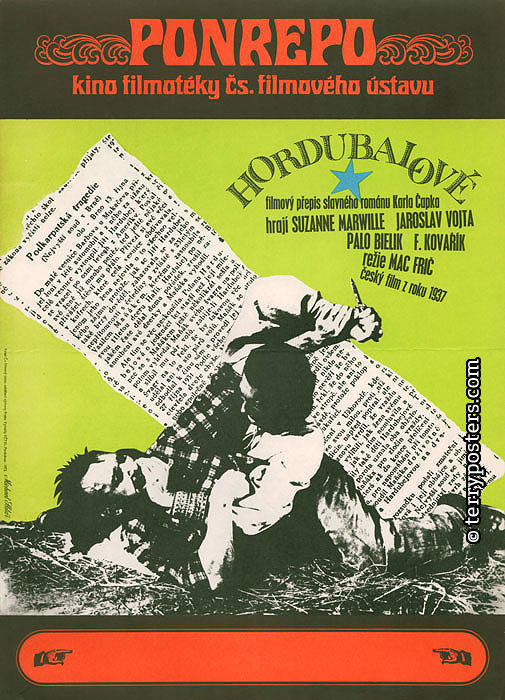

One glance at Martin Frič’s The Hordubals (1937) and the attention is drawn to the multiplication of the title of Čapek’s novel (although the length of a novella, historians specializing in Čapek’s work treat it as a novel, which is why I follow this in my text) from 1933. This ballad of a man suffering from inner loneliness was made into a film in 1979 as well by Jaroslav Balík with the screenplay by Václav Nývlt. However, this study will focus only on Frič’s film.

Karel Hašler figures as a scriptwriter in the credit list (with Frič’s assistance), but all the sources speak for the film being a work also by Čapek himself. First of all it is certain that he did not protest against adding new characters (unlike in Haas’s The White Sickness, in which both artists had a dispute about including a character of Galén’s friend Martin). Application of the hero’s brother on the original text will be the axis of this comparative study as well as characterization of central figures through their visualisation that is connected to every film adaptation of literature, and differences or parallels within narrative structure of both works.

Palo Bielik as the Main Change to the Original Novel

Juraj Hordubal’s brother makes an appearance at the end of the novel without any previous mention of his existence. The motivation is for him to become a guardian of orphaned Hafie, Juraj’s daughter. However, brother Michal plays a central role in many aspects in Frič’s movie as we are witnesses to scenes that have been changed compared to the original novel, or have even been added. Generally known explanation of this phenomenon has very little to do with artistic vision of the production team. Reasons are solely of commercial nature – it was necessary to cast Palo Bielik in the film, but he was simply too young for the character of ageing Hordubal. Lloyd Film Company wanted to benefit from popularity of the hero of famous Jánosik, Frič’s two-year older adventurous film opus. Michal’s character was created solely because of that. The director himself criticised the decision later as he felt it harmed the film and the novel as well. His scenes prevented to make more space for Juraj and his psychological development. (The second thing that Frič did not like was the Company’s decision, also for the commercial reasons, to record the film in Czech language, although it takes place in Slovakia and it was shot at Slovakian locations. It was held against the film also by some audience (not only the Slovakian one) according to the period press.) According to Viktor Kudělka the consequence was that “a noetic work became an adventurous entertainment and criminal affair”.1

Juraj Hordubal’s brother makes an appearance at the end of the novel without any previous mention of his existence. The motivation is for him to become a guardian of orphaned Hafie, Juraj’s daughter. However, brother Michal plays a central role in many aspects in Frič’s movie as we are witnesses to scenes that have been changed compared to the original novel, or have even been added. Generally known explanation of this phenomenon has very little to do with artistic vision of the production team. Reasons are solely of commercial nature – it was necessary to cast Palo Bielik in the film, but he was simply too young for the character of ageing Hordubal. Lloyd Film Company wanted to benefit from popularity of the hero of famous Jánosik, Frič’s two-year older adventurous film opus. Michal’s character was created solely because of that. The director himself criticised the decision later as he felt it harmed the film and the novel as well. His scenes prevented to make more space for Juraj and his psychological development. (The second thing that Frič did not like was the Company’s decision, also for the commercial reasons, to record the film in Czech language, although it takes place in Slovakia and it was shot at Slovakian locations. It was held against the film also by some audience (not only the Slovakian one) according to the period press.) According to Viktor Kudělka the consequence was that “a noetic work became an adventurous entertainment and criminal affair”.1

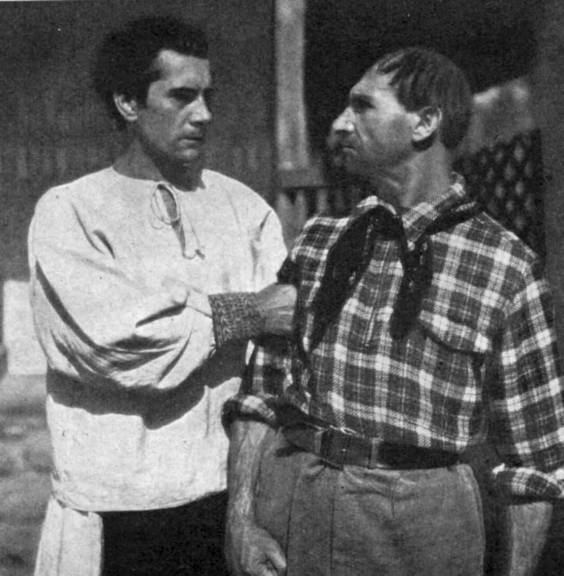

Michal is clearly presented as a hero with heroic features from the very beginning. Audience meets him through a scene from his workplace in a mine where he rescues a fainted boy at the last moment from a certain death of being buried by stones. When Juraj is being beaten up by neighbours after a pub dispute, Michal’s heroic figure steps in and disperses the neighbours without any problems. As Michal is taller and stronger than his brother, it is him – unlike in the novel – who takes charge during Juraj’s conflict with the womanising Štěpán and banishes him from the farm by throwing him over the fence. Needless to mention that all of his actions are shot from extreme low angle, as is done in the case of Bielik’s most famous role. Michal as an audience attraction reaches its heights in a scene that is not motivated by anything, in which he climbs up and down a hardly accessible tree with unnatural speed.

Only small things enable us to find different dimension to Michal’s character. He has debts, but he has a happy union with his girlfriend (later his wife) which creates a crystal clear counterpoint to rich Juraj, who suffers of unrequited love. The brothers’ relationship appears to be problem-free, but only until they fall out with each other because of the unfaithful wife Polana. Apart from the girlfriend Marina, a new character of a nephew is related to Michal. However, he does not interfere with the plot much; and neither does she.

Jaroslav Vojta as Juraj Hordubal

Above mentioned Juraj’s inner loneliness comes mainly from the fact that after his return he has to come to terms with a very different reality from the one that he dreamt of in America during eight years working in mines (his ideas are expressed during the hero’s sleep on a train in the opening film sequence that alternates images from the Western lifestyle and those of his native landscape). His absence caused a significant change in his relationship with his wife Polana who is ignoring him, with daughter Hafie that is unable to find a way towards her father, and the farm’s condition has changed under the dependency of uninvited groom Štěpán. Polana does not return his smile during their first encounter and helplessly runs inside the house, the same does Hafie. On the other hand, both of them greet Štěpán cheerfully when he returns from the field. The exposition clearly sets the situation – everything is different, wrong. Steady situation escalates when Polana protests against Štěpán being fired by locking herself in a room, spending days there not going out and not doing anything. Worn out Juraj then has to take care of the whole farm and look after the daughter.

Above mentioned Juraj’s inner loneliness comes mainly from the fact that after his return he has to come to terms with a very different reality from the one that he dreamt of in America during eight years working in mines (his ideas are expressed during the hero’s sleep on a train in the opening film sequence that alternates images from the Western lifestyle and those of his native landscape). His absence caused a significant change in his relationship with his wife Polana who is ignoring him, with daughter Hafie that is unable to find a way towards her father, and the farm’s condition has changed under the dependency of uninvited groom Štěpán. Polana does not return his smile during their first encounter and helplessly runs inside the house, the same does Hafie. On the other hand, both of them greet Štěpán cheerfully when he returns from the field. The exposition clearly sets the situation – everything is different, wrong. Steady situation escalates when Polana protests against Štěpán being fired by locking herself in a room, spending days there not going out and not doing anything. Worn out Juraj then has to take care of the whole farm and look after the daughter.

Karel Čapek managed to create Juraj Hordubal as a nearly archetypal character for which it is difficult to find functional parallels. Bohuslava Bradbrooková, a theoretician specializing on Čapek, describes him as “a humble, patient and credulous, maybe a little primitive villager”.2 Regardless of his emphasized experience from abroad he still represents a prototype of a simple villager. Funny mangled American words only confirm this. His attempt for a non-Slavonic speech is also accompanied in the film by an nearly Western hat and a scarf around his neck. In general, it is not difficult to see Juraj as a warm-hearted man. His stinginess is only caused by an honest attempt to make his family secured and respected. Jaroslav Vojta’s acting needs to be praised here. Juraj presented for him one of the few strong characters and it is thanks to him that the audience does not laugh to his naivety and does not consider it highly improbable. This was obviously a huge risk because of the visualisation of such a character.

His nature becomes evident mainly through his blind relationship with Polana. Her infidelity is more than apparent from the very beginning. What is more, the truth about the real condition at the farm during those eight years is soon revealed unscrupulously by one of the landowners in a local pub. But Juraj prefers causing a brawl to letting his obstinacy be broken. It could be said that the more of those denunciations, the stronger is his obstinacy. He even glimpses Polana’s and Štěpán’s reunion from afar during a storm montage sequence, but at least for the sake of appearance, he is mollified by the wife’s stupid excuse. However, he falls mortally ill soon, apparently under the pressure of irreversible evidence. Film portrayal of this sequence becomes one of the few moments when the film direction draws attention to itself as the hero’s troubled condition is simulated by distinctive camera angles.

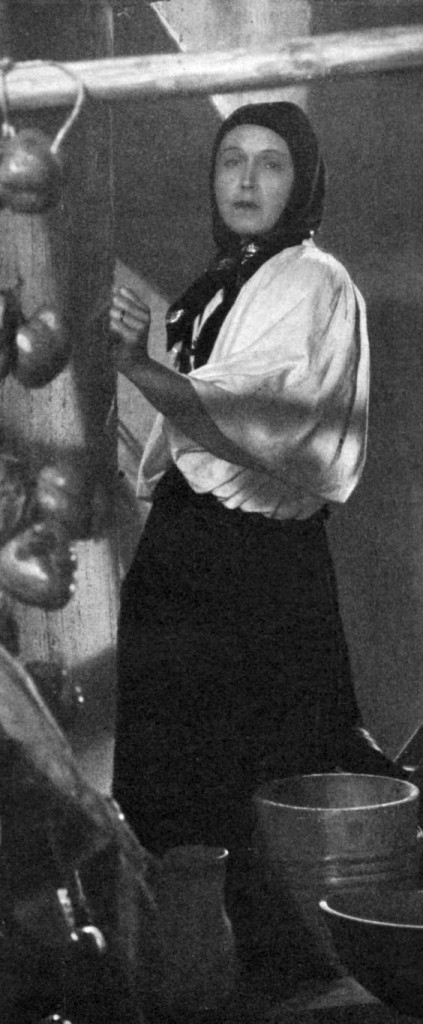

Changes in characterization of other figures are also limited to partial differences. While Polana is described by neighbours as uncontrollable, bony and prematurely aged in the novel, she is played by beautiful Suzanne Marwille in the film. This is the only significant opportunity for the silent film star in a talkie film – silent Polana must have suited her completely. Second change has been in the relationship of Juraj to his daughter Hafie, which remains neutral (to say the best), while here they find a way towards each other. Hafie also explicitly ceases to be fond of Štěpán as she senses the iniquities in her mother’s behaviour, and thus she clings to her “nice daddy“.

Narrative Structure of the Novel and the Film

The novel‘s framework has been transformed into the film version in its complete form; it lacks only Juraj’s visit of Štěpán’s family when trying to solve the whole situation by an engagement of the groom with his daughter Hafie. The film also follows Čapek’s narrative structure and the only visible change is represented by the added scenes with Michal.

The novel‘s framework has been transformed into the film version in its complete form; it lacks only Juraj’s visit of Štěpán’s family when trying to solve the whole situation by an engagement of the groom with his daughter Hafie. The film also follows Čapek’s narrative structure and the only visible change is represented by the added scenes with Michal.

The novel consists of three chapters; the first one, considerably longer than the other two, holds together mainly through Juraj’s inner monologues. Everything is viewed through his perspective. That is why the boundary between visions and reality is erased. The Hordubals take over this element only at the beginning, when the main hero introduces the plot to the audience by summarizing basic premises out loud in an empty train compartment.

At the beginning of the second chapter we suddenly learn that Juraj has been murdered and Polana is expecting a baby, while all are aware of the fact that she must have got pregnant before her husband’s arrival. The perspective is changed; the investigators Gelnaj and Biegl become main characters. The genre is altered in a rapid way; a psychological drama becomes classic detective story surprisingly unfolding without the motif of a locked room. And the third chapter witnesses the change of the genre again – court drama is marked by the plot being anchored inside a courtroom. Štěpán and Polana automatically become the suspects and despite several ambiguities, they are sentenced to a long-time imprisonment at the end.

However, the situation is different in the film. Michal is seen at Juraj’s by one of the passers-by on that fatal night and so he becomes one of the main suspects. The following events are also slightly changed, e.g. the investigation itself resembles a search and pursuit of Juraj’s brother and individual proofs are presented only at the court. Here Polana breaks down under the pressure of conscience and confesses (after which Michal impatiently breaks his handcuffs without much effort). Together with Štěpán she is found guilty and they are convicted of the murder. The last shot shows Michal’s and Marina’s kiss and creates a vision of a classic happy-end of adventure films, let’s say those with Douglas Fairbanks as a main character.

Period critics clearly (fully) acknowledged Jaroslav Blažek’s cinematography. His praising shots of Czechoslovakian landscape to some extend foresaw the shots of similar locations in some films of the Protectorate. Although the film was appreciated by audience abroad (among others at the festival in Venice), it failed in the native country. Even though the critics considered it a disappointment, still it proved to be an above-average quality contribution to the then mostly retrogressive production. Rumour has it that Čapek’s disagreement with Miloš Havel was the cause of the film’s failure with the audience.3 There are thus several reasons why the writer’s influence upon The Hordubals cannot be labelled as peripheral, or even marginal.

The Hordubals

Director: Martin Frič

Script: Karel Hašler, Karel Čapek

Cinematography: Jaroslav Blažek

Original Score: Miloš Smatek

Editor: Gina Hašler

Starring: Jaroslav Vojta, Palo Bielik, Suzanne Marwille, Mirko Eliáš, Eliška Kuchařová, Vlasta Součková, František Kovářík, Filip Dávidik, Gustav Hilmar, Vilém Pfeiffer, Alois Dvorský

Opening Night: 21st January 1938, Czechoslovakia, 95 mins.

From the Czech original translated by Barbora Greplová

- KUDĚLKA, Viktor. Čapkův přínos českému filmu. Film a doba 1988, nr. 4, p. 201. [↩]

- BRADBROOKOVÁ, Bohuslava. Karel Čapek. Hledání pravdy, poctivosti a pokory. Praha: Nakladatelství Academia, 2006, p. 106. [↩]

- FIALA, Miloš. Martin Frič. Muž, který rozdával smích. Čechtice: Nakladatelství BVD, 2008, p. 129. [↩]