„To put 2 000 years in 10 minutes was a distillation process“

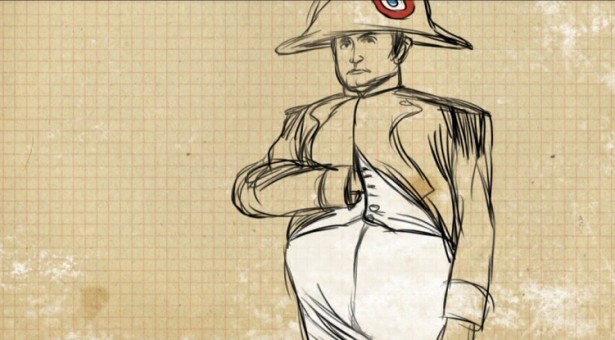

Volker Schlecht is a Berlin based animator and illustrator, who created three animated short films, the latest being Germania Wurst (2008), sharp and ironic treat on German history in a nutshell, which got many awards at film festivals. But Volker Schlecht is also an acclaimed illustrator, together with Alexandra Kardinar he illustrated two awarded books: The Soul of Motown (2009) and Das Fräulein de Scuderi (2011). But his numerous illustrations, design and typography works appear also in magazines, on websites and in museums. In this e-mail interview Volker talks about what it takes to be independent animator and illustrator in Germany, his experience with Barrandov Studios and his view on rotoscopy.

Volker Schlecht is a Berlin based animator and illustrator, who created three animated short films, the latest being Germania Wurst (2008), sharp and ironic treat on German history in a nutshell, which got many awards at film festivals. But Volker Schlecht is also an acclaimed illustrator, together with Alexandra Kardinar he illustrated two awarded books: The Soul of Motown (2009) and Das Fräulein de Scuderi (2011). But his numerous illustrations, design and typography works appear also in magazines, on websites and in museums. In this e-mail interview Volker talks about what it takes to be independent animator and illustrator in Germany, his experience with Barrandov Studios and his view on rotoscopy.

Česká verze rozhovoru je zde. / Czech version of the interview is here.

You studied communication design under prof. Eva Natus-Šalamounová at the University of art and design Halle. How much did this education enrich you in terms of skills and inspirations?

The time at the Burg Giebichenstein in Halle was a very inspiring time for me. Not only because of Eva Natus-Šalamounová, but she was responsible for animated film and illustration. She also gave us the possibility to come to Prague, to see the Barrandov Studios and to work over there, to get in touch with all these fascinating people there and this extraordinary world of great puppet and drawn animation. Moreover, she opened our minds for international animated short films, for festivals and all these things, for Švankmajer, the Brothers Quay, Aardman, Schwizgebel, Raimund Krumme and any other great gurus of animated film. I owe her very much, personally as well. There would be no Rue Rosé or Sonst nichts without her.

Your mentioned your short films Rue Rosé (1996) and Sonst nichts (1999), which were produced at Barrandov Studios. How do you rate this experience? And are there legendary Czech animators you particularly admire?

To work at the Barrandov Studios was really great. They gave me a room to work there, to draw, to animate. I had a real professional workflow, with support. Despite almost no Czech language skills, to be there was like a dream. Everyone was kind, the staff was like a small family there. And the same people who made all these great films were working on my films, and I was part of all that — that was unbelievable!

I am a great admirer of the works of Jan Švankmajer. I love the work of Barta, Pavlátová and Koutský as well. But unfortunately I don’t know enough about the great tradition of puppet animation and about Jiří Trnka, Břetislav Pojar and Hermína Týrlová, that’s a pity. I just have a little collection of books illustrated by Trnka.

Could you tell me more about Rue Rosé (1996) and Sonst nichts (1999)? The first one is connected to your studies at Halle university, I suppose. About the second I know almost nothing. Is there some continuity between these two and Germania Wurst (2008)?

You are right, Rue Rosé was my diploma work, the film I finished my studies with. In addition, it was my first film. Since I did not study animation, but graphic design, animated film was only a part of the illustration lectures in the whole schedule. So I tried to make a film with quite basic skills of animation and put a kind of philosophical idea around it — I tried to get metrage as much as possible from a very limited input, it is not much more than a sequence of different walk cycles.

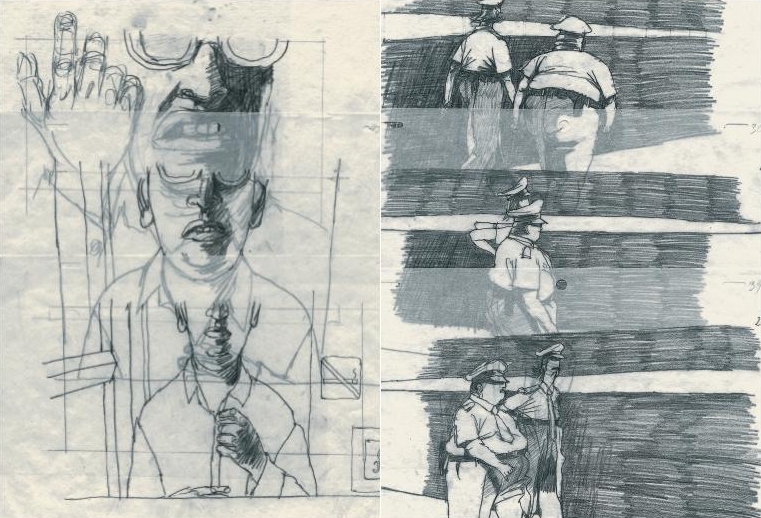

The connection between those two films was the intention to do the complete opposite in Sonst nichts as compared to Rue Rosé: The story is quite a non-story, two people meet each other by accident and nothing happens, that’s all – nothing else (Nothing else is the English title of the film, it’s the translation of Sonst nichts). The film is very short, less than 3 minutes, but for more than a year I put all my energy in it, and made very complex drawings and some sophisticated virtual camera moves. It was an experiment: to make a piece of art out of a very small and unspectacular content of daily life, through the transformation in drawn animation. I hoped it could be a little bit like painting a still life out of nothing but some apples (like Cézanne) or an old toy or withered flowers (like Horst Jannsen).

Furthermore, both films are made with the same technique, using the same material, they both were recorded with the same analogue camera, and were produced by the same people at Barrandov.

Between the two films and Germania Wurst were more than 8 years. There is not so much continuity apart from my way to draw and to animate things. The simplicity of background design and the reduced colors are also alike. But the content, the idea, the research and the way of telling the story were much more complex in Germania Wurst, as compared to the two other films.

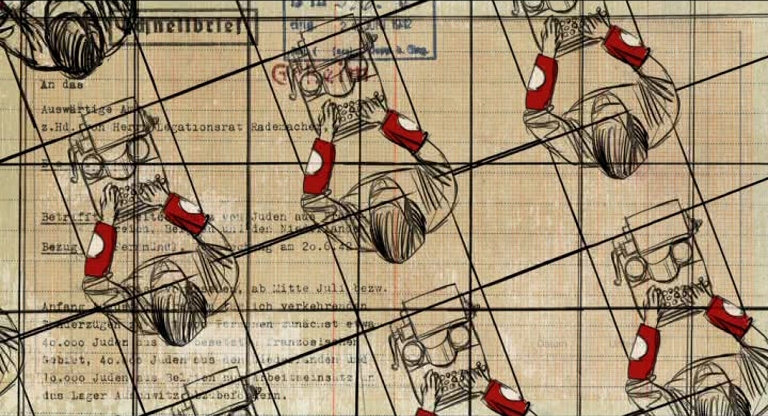

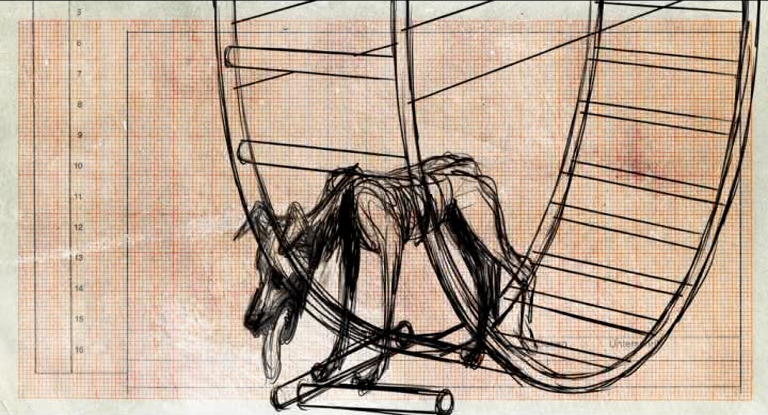

Walking and – let’s say – machinery seem to be recurring themes of your work, as well as using documents (archive materials) and other materials in the background, which in Germania Wurst is not only good looking, but most importantly it adds another layer to the story…

Walking and other cycles in animation present a chance to overcome the frustration about making so many drawings for so little of screen time. That’s why I often try to make cycles and to re-use sequences and scenes. But I also like walk cycles because I love to draw people and to characterize them with a specific movement. This was the aim of Rue Rosé. Using documents as background layers in Germania Wurst I had exactly these intentions in mind: they add another layer for understanding the story or for thinking about the story in a different way, and of course these documents and paper materials are a natural background for drawings.

How did the idea of Germania Wurst – history of Germany in wurst – came to you? It is quite merciless, very precise in terms of rhythm, it uses music which accompanies images, constantly changing through metaphors and associations from one to another…

I’m very interested in history, not only in German history. So I asked myself: why don’t you make a film about that? Germania Wurst was an experiment, to put 2 000 years in 10 minutes. I thought, it could be a good challenge for my way of doing animation: I was forced to use metaphors and an associative way of telling the whole history, and I had to think about the whole and complex stuff in a very distant and analytic way, it was a kind of a distillation process.

Germania Wurst was successful, it received awards at many festivals. I would guess festival audience is enjoying it. But what kind of reactions did you have from older German spectators?

I got no special feedback from older German spectators. But I don’t know if there is a meaning behind that fact. For me the geographical differences of festival reactions were more interesting: I got many invitations and awards in the eastern part of Germany, the former GDR, and much less invitations from festivals of the western part, also no invitations from France, but many awards in Spain.

You were the only animator of Germania Wurst, which seems to be like a hell of a work. Could you describe the process of making the film – why did you choose to use rotoscopy, what programmes did you use and how long did it take to make this film?

Maxim Vassiljev made additional animations for some scenes, but you are right, most parts of the film I’ve drawn by myself. Of course it was a lot of work, like any other animation. I drew it digitally on a Wacom Cintiq and used Plastic Animation Paper, Animo, and finally Adobe After Effects. I worked on it from 2005 to 2008, but mostly not the whole day. From 2002 to 2007 I worked as a teacher of animation at the HFF Konrad Wolf, the film and television university in Potsdam-Babelsberg, where I could make this film as part of my work. The university produced it, too. So, if I had to calculate the real time of working on this film, I would say two years or one and a half.

But there is a misunderstanding: I didn’t use rotoscopy! The first time ever, and the only scene in Germania Wurst I used rotoscopy for, is the scene with the marching Prussian grenadiers. There I tried to use a sequence from Barry Lyndon by Stanley Kubrick, but it wasn’t very helpful.

I see. Then what is your opinion on rotoscopy from the position of animator and spectator? Do you like some rotoscoped films?

I think rotoscopy can be dangerous, but sometimes helpful. If you don’t have any classical animation skills and think you can use rotoscopy as an easy way to make a film, which looks like drawn animation, the movement will be mostly boring. But if you use rotoscopy as a supporting tool to make some sequences more „photorealistic“, and if you know about the dangers, it can be helpful. I used it for my last production, a music video clip. The problem is not far away from using photographs for paintings, drawings or illustrations, as I also do: if you’ve learned to draw without this kind of „crutches“, you may know what you do, and the photograph can be a helpful thing – in my opinion. But you can see bad examples every day, in magazines, advertising and other media.

How difficult it is for animator and illustrator to establish himself in Germany without taking jobs which would be aesthetically and morally against his conviction?

I can only speak for myself and a little bit about the few people I know. I would say it is possible to live, but more or less impossible to plan your life. Many people try to get a professorship at an university to have a bit more safety, but then they have less time to make their own professional work. Without this „backup“ most people have to be pragmatic: the „nice“ and interesting jobs like book illustration or magazine illustration are not well paid. If you can work for advertising agencies, you can make more money. But where is the personal borderline for aesthetical and moral convictions in this business? I believe it depends on your personal financial situation, and this is a normal human thing. In animation it is not exactly like that. For instance the German film funding for independent filmmakers who are successful on festivals is quite comfortable, I would say. But „out there“ in business it is the same, advertising and other commercial or corporate jobs are quite the only possibility to get well paid. The cultural and the public sector is poor. Especially in Berlin we do have the so called „Berlin Economy“. The rents for flats and studios are much lower than in Munich, Cologne or Frankfurt because of the – in comparison to these cities – weak economy, and therefore, sometimes you are able to work on cultural jobs and make cool things which are badly or not paid. This fact is one of the most important backgrounds of the „glamour“ of Berlin.

You and Alexandra Kardinar are Drushba Pankow. You work on various projects, one of them being Das Fräulein von Scuderi, your graphic novel / illustrated version of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s famous story, set in 17th century. The illustrations look really rich and the book itself looks just great, not to mention your typography work etc. It seems to me that you are developing your style, kind of collage-like, which is very distinctive…

Thank you very much ;-) The look of these illustrations and books is developed as a result of our permanent exchange. Our „professional partnership“ is not only harmonic, sometimes even very controversial, but it is always a kind of engine. Sometimes we call our working process „creative ping-pong“, but ping-pong sounds a little bit harmless… We both studied graphic design and illustration in Halle, both under Eva Natus-Šalamounová, so our base of skills and „convictions“ are quite the same. But our temperaments and personal backgrounds are very different, and so these „ingredients“ produce our mixture of illustration „styles“, which are also – of course – changing and developing.

What are you working on now and what are your future plans?

Our latest project was a music video clip. We hope we will have a chance to show it on some coming festivals. It is also completely drawn animated, and for the first time we tried to transform the look of our book The Soul of Motown into animation – from illustration to moving pictures. For the future we plan to make a new animated film, but connected with a new book project.

Source of V.S. photo: filmkunstfest-mv.de

Komentáře (1)