Die Leiden des Jungen Dominik

After first watching Sala samobójców I felt (as well as many young people do) that it was about me or at least about part of our generation – losers having locked up themselves in imaginary worlds, suffering from a spectrum of psychical disorders starting with social phobia and ending with borderline personality disorder. However, after watching this movie several times, my relation to it evolved or actually commuted. Initial rigid fascination was substituted by a skeptical point of view and now it is in a phase of ambivalent approach to the movie. The reasons why it happened so are to be discussed in this critical essay on the movie.

The movie Sala samobójców was first released at Berlin International Film Festival, 12th February 2011. Polish first run took place in Warsaw on 28th February. Cinemas showed the movie on 4th March. In April 2011, it was awarded by FIPRESCI (International Federation of Film Critics) at OFF PLUS CAMERA International Festival of Independent Cinema (in Poland). In November 2011, the movie won a prize Złote Kaczki awarded by the readers of “Film” in three categories: Best Movie, Best Screenplay and Best Movie of 2010/2011. Moreover, Jakub Gierszał got the Best Actor (in a leading role) award for his performance in the movie.

Director Jan Komasa graduated from The Leon Schiller National Film, Television and Theatre School in Łódź. He was awarded for his short student film Fajnie, že jestes in the Cinefoundation competition in Cannes. Komasa also participated in making a narrative movie Oda do radości, which was awarded by the Jury Prize at the 30th Polish Film Festival in Gdańsk and was shown at festivals in Rotterdam and Karlovy Vary as well. In 2007 Komasa made a full-length documentary Splyw, but Suicide Room is his full-length feature debut.

A viewer is entering the movie accompanied by opera and flashbacks that introduce individual characters – Dominik and his parents. An opera motif itself suggests their belonging to higher social class. Father works for a government department, mother is employed by a design company, their only child Dominik has got his own driver and is cramming Hamlet’s role (ironically, Dominik becomes sort of a Hamlet to himself later). Everything in Dominik’s life pertains to the norm. He and his parents are like slaves following the orders of the capitalist industry. Yes, they are rich, but in order to do so they have obeyed the norms for so long that they can no longer feel free. Also Dominik’s character is right from the begging very difficult to read. Film promotes him very heavily as a „normal boy“, which is a big mistake – Dominik is not normal, he is unique – not like most viewers and Sylwia, who is, as representative of a middle class, living in prefabricated district . Dominik comes, taken from the material point of view, from the society of rich and beautiful people, and he can have anything he wants. But he is like (emo)prince, locked in the glass castle.

In contrast to Dominik himself, the real world in the movie is not isolated. The story can take place in any advanced capitalist (European?) country. Spatial and cultural limitlessness enables a cosmopolitan application of the subject. That is why the slogan to the movie is that right – Takiego filmu jeszcze w Polsce nie było – such movie has not been made in Poland yet.1 It is connected to Poland only via the language used. Maybe just because of this, the movie became popular in the western countries.

Life of the family runs like a well-oiled machine until a wrong wheel is set inside. That is when Dominik realizes that he’s not a machine, or rather that he’s not able to work like a (pretty spoiled though) machine. His sexual “accident” with a friend during practicing judo completely destroys his way of real-life existence. We can discuss here whether it is caused by the fact that adolescence is always difficult; hormonal changes and new feelings can destabilize anyone. Dominik bends the standard of clear heterosexuality, even though we don’t find out during the whole movie (which is evidently not its aim), whether his homosexuality was just a desperate hunger for real closeness, a part of bisexuality or just an attitude being used.

Poor dear young Dominik has it all – private schools, fancy gadgets and money. Unfortunately for him, his world is full of expensive things, but emotionally empty. In reality, everything, even the friendship of his classmates, is possible to buy. At the same time a reality is large and empty like his darkened room, where only a computer monitor is blinking. No surprise that the reality stands on the same level as Dominik’s Facebook profile. The answer of Dominik to a meeting with the evil side of reality, his accident during judo, is a classical defense of emotionally isolated but on the other hand spoiled individuals – hysteria behind which a desire for someone close to chat with is hiding. The parents, acting like real machines and not people, are not able to provide Dominik sufficient emotional background. Dominik doesn’t know how things work in real world, so he comes back to the Internet and finds here substitutionary world for the real or pseudo-real Facebook world.

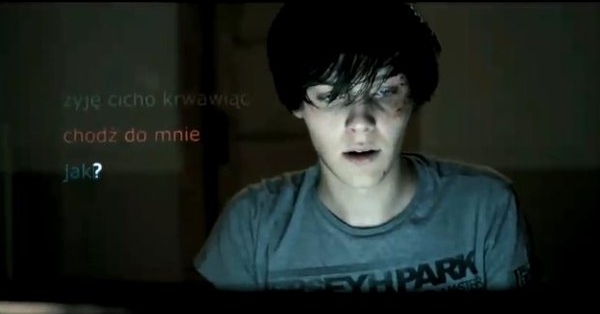

At that moment of Dominik’s desperation Sylwia appears on his chat list. From the beginning, they are connected by the sympathetic felling, so he contacts her again and joins the group called „Suicide room“ in an on-line virtual world reminding Second Life. The world itself is enticing and well-conceived, creating the necessary atmosphere to invite us into this alternative life. The more Dominik escapes from real world, the more he develops his character in the virtual world. At first, his avatar is his perfect physical embodiment, but later he creates fighter avatar and still later, at the end of the movie, he develops into some kind of goth-lover. However, these sequences fail to bring in the necessary completion to the story. Mainly because of two basic flaws. Firstly, in spite of the fact that Sylwia is the queen of this virtual world, her reign is nothing, but irritating mannerisms. The second reason is absolutely no internal policy of the inside world of the „Suicide room“. At first, Dominik seems to be an intelligent boy. Then I couldn’t believe that he could be manipulated so easily. Just at this moment, when Sylwia’s brainwashing had begun, I started to feel the ambivalent chemistry of the film working upon me and I gained the feeling that the only person with common sense in both worlds (virtual and real) is avatar Jasper, who says before the virtual execution: „She has brainwashed us.“ I think, Komasa tries to do the similar thing. In the next part of my essay I want to focus on the style, compositional illogicalities and mistakes of the film.

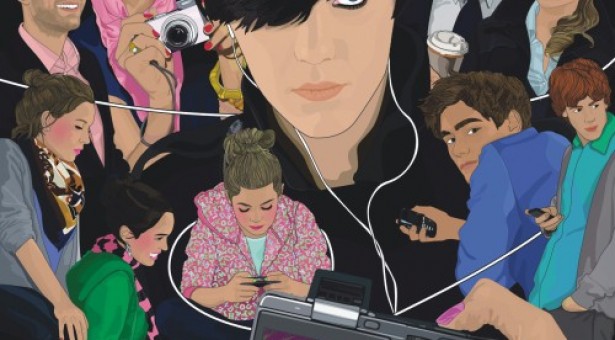

Komasa admits in one Czech interview2, that he is fond of Emo and Goth(ic) style and Twilight tetralogy, therefore he used some elements of those styles in his film. The style of the film is really distinctive. Most of the scenes take place at night and the color spectrum oscillates between dark shades of blue and black. The style also uses some elements typical for west/global production. Visualization of thoughts/written texts in mise en scene, split screen during webcam chats, and the same visual style in virtual world as in Japanese anime are used. Many scenes work well as a videoclips thanks to the music by Billy Idol and Wet Fingers and to the cool look of slow motion. Thus, the visual side of the film looks very spectacular, dark and emo, regardless of stylization of Dominik, who, even before his indoctrination by Sylwia, represents a typical example of emo boy from vampirefreaks.com website or something like that. Sometimes, the style seems to be inconsistent with the idea of the film, which (I hope) tries to be anti-suicidal. There is a question, whether Komasa wants to tell a story about alienation as a critique or as a glorification, mainly because the style of the film definitely supports the second choice. So, there is no wonder that most of the fans of this movie are young people aged x-teen (or older, me being the example). This fact can be easily verified by the average age of the voters on IMDb, by fan videos on YouTube or by searching the information about the film on blogs. There is therefore no surprise when Sala samobójców is on their blogs next to My Chemical Romance videos, notes about difficult adolescence and slash fiction.

The final part of the film gradates ad absurdum. Dominik, before he finally loses the rest of his common sense, tries to talk Sylwia out of committing a suicide, but after a spectacular bloody cybersex (?) he submits to her. In the manner of deus ex machina, angry and desperate parents (played very stereotypically throughout the film as very bad and helpless parents) stop the existence of virtual world when they disconnect Dominik’s computer from the Internet which later on will cause actual and permanent “disconnection” of Dominik from his real life.

The naturalistic epilogue with the recording of his death was, at first, the strongest moment of the film for me, until I realized that it’s absolutely impossible the death of young man to be uploaded (and not to be immediately deleted by the admin) to video-sharing website looking like YouTube. Ironically, with comments of other users and, most paradoxically, via Dominik’s own user account. Who is watching the video then? His mother? Or father? Both of them? Anonymous audience? Another interesting thing is also the date of uploading the video. Sylwia’s self-harming video showed at 11th April 2011, when Dominik was commenting it. But Dominic’s suicide video was uploaded on 4th March 2011, which practically means traveling back in time. Of course this is a small compositional mistake which can be easily overlooked, but for me it was an icing on the cake whose dark and desperate style dominated the story to such an extent that any deeper meaning was lost in spectacular demonstration of tawdry stereotype. So, Dominik’s sorrows and his death are not such as those of Hamlet, as it seemed at first, but rather such as those of young Werther. They are impressive, dangerously influencing, but, after deeper thought, absolutely unnecessary.

Sala samobójców

Director and screenplay: Jan Komasa

Cinematography: Radoslaw Ladczuk

Music: Michal Jacaszek

Starring: Jakub Gierszal (Dominik), Roma Gasiorowska (Sylwia), Agata Kulesza (Beata), Krzysztof Pieczynski (Andrzej), Bartosz Gelner (Aleksander), Danuta Borsuk (Nadia), Piotr Nowak (Jacek), Filip Bobek (Marcin), Kinga Preis (Karolina), Anna Ilczuk (Ada), Bartosz Porczyk (Tomek), Piotr Glowacki (Darek), Aleksandra Hamkalo (Karolina), Krzysztof Dracz (Minister of Foreign Affairs), Paulina Chapko (receptionist), Krzysztof Czeczot, Karolina Dryzner (Jowita), Rafal Fudalej (Sirius – voice), Karolina Kominek Skuratowicz (Kreska – voice), Mateusz Kosciukiewicz (Jasper – voice).Poland, 2011, 117 min.