Art and Text: How something primarily to be looked at turned into something to be especially thought about

In 2009, British publishing house Black Dog Publishing, focused mainly on “beautifully illustrated books which represent a fresh, eclectic move on contemporary culture” as well as on books of Art, Architecture, Design or Environmental issues,1 first published a book which soon became one of its most popular bestsellers: Art and Text. The book is mapping the onset, the development, roots and the broader social, artistic and philosophical context of an alphabetic text in the contemporary art.

At first glance, its respectable size, glossy paper, hard cover, bold graphic design, registers and a precise formal processing creates an impression of a quality publication.

From poem to neon

Art and Text is designed as a comprehensive visual guide supplemented by three academic essays approaching history and manifestations of the changing relationship of artists to the text during the 20th and 21st century, from the works of visual poets, through the avant-garde of the twenties, the artistic movements of the sixties to the present.

The essays by Will Hill, Charles Harrison and Dave Beech 2 approach the phenomenon in the context of Art History, Philosophy of Language and Linguistics , thus creating a suitable background for understanding the main, visual part of the publication. (However, they require some basic knowledge of the art history and linguistics from readers.)

After an introductory essays’ section, the publication is divided into four parts organizing the artworks according their relationship to incorporated text: Text, Context, Semiotext and Textuality.

In the chapter “Text”, there are works examining the text as material, medium and/or subject matter, for which is typical rather uncomplicated and straightforward use of language, and instructional, stereotypical and systematic structuring of the work of art.3

Mel Bochner: Language Is Not Transparent, 1970

chalk paint, 183 x 122 cm

There are represented artists such as: Laurence Weiner, Richard Long, Carey Young, Mel Bochner, Doug Aitken, Catherine Street, Russell Crotty, Aldo Chaparro, Raymond Pettibon, Jeremy Deller, Ed Ruscha, Jack Pierson, John Baldessari, Martin Creed, Stephan Brüggemann, Bob and Roberta Smith, Simon Morley, Matthew Higgs, Mustafa Hulusi, Richard Artschawer, Claus Carstensen, Monica Bonvicini, Paul Sietsena, Ian Breakwell, Ward Shelley, Hamish Fulton, Andy Warhol, Aldo Chapparo, Mario Merz, Lawrence Weiner, Jack Pierson, Matt Mullican, Matthew Higgs and Simon Patterson.

The chapter “Context” is more responsive to social forces. The creators turn to themselves and to cultural identity through art and text. The self-reflexive referring to the art world of which they are part of is also typical.4 We encounter works by The Atlas Group, Gillermo Kuitca, Ken Lum, Liam Gillick, Mel Bochner, Simon Linke, Bob and Roberta Smith, John Latham, Mark Titchner, Adam Dant, Martin Creed, Shirin Neshat, Jason Rhoades, Adel Abdessemed, Glenn Ligon, Barbara Kruger, Jakob Kolding, Gordon Young, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Sean Landers, Donald Urquahart, Jonathan Monk, the art group FREE, Bank, Sam Durant, Jonathan Meese, Jules de Balincourt, Marc Bijl, Nathan Coley, Glenn Ligon, Susan Hiller, Ken Lum, Nancy Sper, Aleksandra Mir, Matt Mullican, Guerrilla Girls, Simon Bedwell, Claire Fontaine and Alfredo Jaar.

Marc Bijl: Modern Crisis, 2009

Legal intervention in the Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel

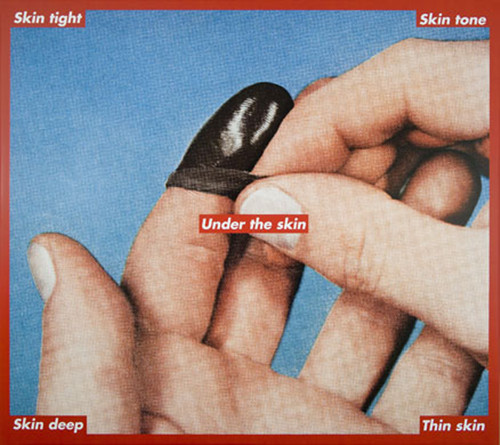

“Semiotext” is affected by modern semiotics and teachings of Saussure, Barthes and Derrida, and a certain loss of faith of the authors in the reliability of the language. The meaning of the text, hence of the words, is suddenly heterogeneous and vague, and a linguistic character is an “uprooted, wandering element” which by itself basically has no meaning.5 Here, Aimee Selby puts some works by John Baldessari, Martha Rosler, Peter Downsbrough, Tauba Auerbach, Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sulliven, Barbara Kruger, Simon and TomaBloor, Lawrence Weiner, Peter Downsborough, Joseph Kosuth, Kay Rosen, Gary Hill, Anne-Lise Coste, Cerith Wyn Evans, Robert Smithson, Simon Patterson, John Baldessari, Ian Breakwell, Art & Language, Doug Aitken, Victor Burgin, John Latham and Christopher Wool.

Barbara Kruger: Untitled (Skin tight/Skin tone/Under the skin/Skin deep/Thin skin), 2007

digital print / vinyl, 265.5 x 289.5 cm

Finally, the last section of the publication titled “Textuality” treasures works examining “textuality” of the text, which refers to the variation between the lack of transparency and clarity, a sort of fluid status, indefiniteness. This chapter includes authors such as Richard Prince, Claus Carstensen, Fiona Banner, Catherine Street, Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sullivan, Allen Ruppersberg, Simon Popper, Marc Bijl, Hayley Newman, Jeffrey Shaw, Gary Hill, Glenn Ligon, Robert Barry, Olivia Plender, Roni Horn, Jeffrey Shaw and Dirk Groeneveld, Simon Patterson, Douglas Gordon, Carey Young, Jeremy Deller, Xu Bing, Carolee Schneemann, Tom Philips, Simon Lewty, Hanne Darboven, Allen Ruppersberg, Mel Bochner, Cerith Wyn Evans, Daniel Pflumm, Jens Haaning, Adam Chodzko, Simon Lewty, Roni Horn, Svetlana Kopystiansky, Ugo Rondinone, Cy Twombly, Vito Acconci, Roni Horn, Jaume Plensa.

Xu Bing: A Case Study of Transference, 1993–1994

a performance with two pigs described with false English and Chinese letters, discarded books, cage 5 x 5 m. Performance in the artistic heart of Han Mo in Beijing, January 22, 1994

If the logic of linguistic systems was revealed to be an elaborate, always contingent set of already-established codes and ideological constructs, it followed, then, that not only was the relationship of signifier to signified in jeopardy, but the relationship of text or literary form to itself, might too be perceived a inherently heterogenic and always in crisis.”6

Each of the sections, consisting of a generous visual documentation of most Anglo-American art from the 1960s to the present, is provided with a professional and a highly intelligible one-page preface.

The visual part is then permeated with the broader occasional notes on individual works and their authors. There is still plentiful text in the publication – after all, the documented artworks themselves often contain large amounts of text to read or stories which the reader must “get through”.

Art as thought

Rather than something primarily to be looked at, the work of art would be conceived of as something to be thought about. 7

In the relationship of written word and visual arts, there were several crucial points in the history of the 20th century: the avant-garde movement of the 1920s and 1930s, 1960s conceptualism, aesthetic after-Duchamp ready-made and appropriation. This turn to the text in art was determined by the linguistic turn in philosophy which happened in several waves. As Dave Beech summarizes in his essay,8 the first generation of artists who devoted themselves to the text, such as Art & Language, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner and others, was motivated by the analytic philosophy of Wittgenstein, Austin, Willard Quine and AJ Ayer. The second generation (Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Kay Rosen, Raymond Pettibon) was influenced by the structuralist and post-strukturalist theories of language, teachings of Ferdinand de Saussuer, Roland Barthes, Derrida, Jacques Lacan. For their followers (Patterson, Bob and Roberta Smith, Titchner), the linguistic turn only serves as a kind of background manifested in the contemporary art.

The first text-oriented works of the 20th century were all typographical experiments of poets such as Kurt Schwitters, Guillaime Apollinaire or Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.9 The inclusion of the text represented a major conceptual breakthrough in the contemporary art practices. According to authors of the publication, the discovery of the new “media” was the answer (and parallel) to the spreading feeling of disillusion which the modernist painting has provoked, and since the rise of conceptualism in the 1960s, it is about far “deeper and more significant mode of thoughts” than a mere diversion of the aesthetics of visual artistry and imagination.10 The vibrancy of this “ideological mode” is proved by the fact that a significant part of the artistic works presented in the publication comes from either current or imminent time. It is not only a purely visual art works, but also works working with sound – combining spoken and written text, installations, video art, textual instructions etc.

René Magritte: Ceci n’est pas une pipe, 1929

oil on canvas

The book as an object

The graphic and typographic modification of the publication honors its theme. The fine design and literally breathtaking graphic work refers to 1960s Pop Art in which the incorporation of text into art experienced its boom. The inventive solution of the division of paragraphs into text blocks with various alignments makes it easier to read, helping – together with the image accompaniment which is quite radically embedded directly into the blocks of text – visually divide otherwise large amounts of text on the large page (28 x 23 cm).

Thanks to its size and weight, the hard-cover edition of Art and Text is publication designed to be studied in the backgrounds of your study, preferably sitting at an oak table with a glass of wine or listening to the sounds of some piano sonatas. The layout of the graphics clearly counts on this style of reading and tries to make it as pleasant as possible. Then, the excellent news is that during the summer 2016, the “light” paperback edition of the publication has been issued.

From Czech original “Art and Text: Jak se z něčeho, na co se primárně kouká, stalo cosi, o čem se zejména přemýšlí” translated by Ivana Formanová.

MEIXNEROVÁ, Marie. “Art and Text: Jak se z něčeho, na co se primárně kouká, stalo cosi, o čem se zejména přemýšlí” [on-line]. 25fps, www.25fps.cz, Mar 23, 2016. Available at www: <http://25fps.cz/2016/art-and-text/>.

Art and Text

Authors: Dave Beech, Charles Harrison, Will Hill, Kevin McCaighy, Louis Pattison

Editor: Aimee Selby

288 pages, hardcover

272 illustrations, b / w and color

28.0 x 23.0 cm

Date of publication: September 15, 2009

Language: English

ISBN13: 978-1906155650SELBY, Aimee (ed.). Art and Text. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2009.

The hardback Art and Text is still available on Amazon.

The paperback can be purchased directly through the publishing house website Black Dog Publishing.

Other reviews:

PUCKETT, James. “Art and Text”. I Love Typography [on-line]. Feb 2 2010. Available at WWW: < http://ilovetypography.com/2010/02/02/art-and-text/>.

PUCKETT, James. “Book Review: Art & Text. The Intersection of Art”. I Love Typography, Vol. 11 no. 04, March 2011, p. 3 and 8. Available at WWW: <http://issuu.com/jeffinaolga/docs/final_newsleper>.

HUTH, Geoff. “The Art of Text of Art“. Blogspot.com: Geoff Huth [on-line]. Jan 10 2010. Available at WWW: <http://dbqp.blogspot.cz/2010/01/art-of-text-of-art.html>.

- “About Us“. Black Dog Publishing [on-line]. Feb 2 2016. Available at WWW: <http://www.blackdogonline.com/about-us.html>. [↩]

- “The Schwitters Legacy: Language and Art in the Early Twentieth Century” (Will Hill), “Think Again” (Charles Harrison), “Turning the Whole Thing Around: Text Art Today” (Dave Beech). [↩]

- “Text”, p. 37. [↩]

- “Context,” p. 91. [↩]

- “Semiotext”, p. 171. [↩]

- „Textuality“, s. 213. [↩]

- HARRISON, Charles. „Think Again“, s. 22. [↩]

- BEACH, Dave. “Turning the Whole Thing Around: Text Art Today”, p. 31. [↩]

- Foreword, p. 7. [↩]

- Foreword, p. 7. [↩]