Whom Did Jan Forget?

ANALYSIS: And the Fifth Rider is Fear (d. Zbyněk Brynych, 1964) – TOMÁŠ UHER – Translation: TOMÁŠ KOMÍNEK –

Původní článek v češtině je zde. / The article in Czech language can be found here.

The movie And the Fifth Rider is Fear (…a pátý jezdec je Strach), directed by Zbyněk Brynich, was created in 1964 as the middle part of his trilogy subjected with the matters of the Second World War (Transport z ráje / The Transport from Paradise, …a pátý jezdec je Strach / And the Fifth Rider is Fear, Já, spravedlnost / I, Justice), as Brynich later claimed. This time the theme was „a tragedy of an individual who is making a decision“.1

An Apparitional Movie

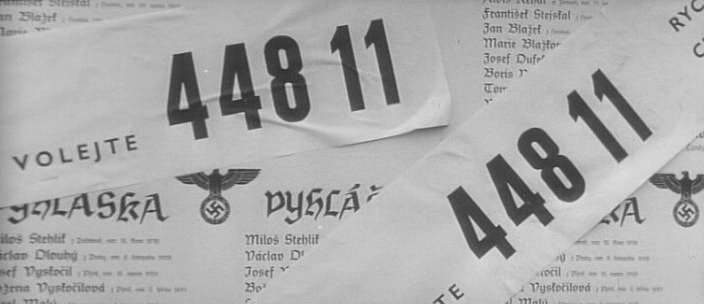

Armin Braun was a doctor, but he’s not practicing this job. He was a human, but his life is not that of a human. Armin Braun is a Jew and everywhere he looks is the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The walls within the Protectorate are covered with appeals for denouncement, even with a phone number to call to trustfully, everyone is being raised to obedience through public broadcasts and Jews are being transported away from their homes in cargo trucks, with the door of those houses being sealed. The Protectorate is inside the people all around him, speaking through their mouths and directing their lives.

And standing on those empty streets are men dressed in black suits, with hats on their heads, appearing and vanishing all of sudden, invisible and yet still near, being the four riders of the Apocalypse and ruling with the force of Fear. The power is anonymous and pervasive, it reproduces itself among the people so that they don’t have to be watched over all the time, the people will watch over each other and even over themselves, they will denounce and believe in the rightness of denouncement. The malevolence does not have to appear at every moment, as every moment is in the hands of malevolence.

The Limbo

The dislocation is hidden in the movie’s space itself. The synagogue is flooded with things, both on the ground floor and the storey, supplanting for people like in the Theatre of the Absurd; together they join in the silent prayers for the owners who are not coming back (even Braun himself is just a sort of a confiscated thing, a fragment of his own life). The synagogue is like a common workplace and the people pretend in all the rush that they are just on a common job. The lonesome Braun, small in every space, is small even in his office, where just a few lone objects hang on the white walls with a black coat between them, looking like a cast-off shadow.

Most of the movie takes place in a single apartment house. An oval staircase stretches from the darkened ground floor, along the five door leading to different apartments, up to the small door in the attic where a single room with coarse white walls (just like in the office) is hidden.

Living on the ground floor is a mentally feeble housemother, who breeds rabbits. Next one is a retired music teacher, whose flat is chock-full with old things, particularly books, like a forgotten refuge of repressed culture. The family of a butcher connected to the resistance movement resides in a confined, shabby and altogether ordinary flat, while the lawyer’s family owns a roomy apartment, abounding in the inter-war republic luxury, antique furniture and objects of art. The last door leads to the flat of a bachelor public defense commander, where piles of newspapers border the walls as an evidence of his collaboration.

The diverse characters from varying social groups occupy together this one house, this small world and their flats, which mirror their positions and lives. Walking around these door time and again every day is the last Jew, left behind out of some unknown cruelty as a witness of the universal decline, outlawed and able of nothing else than waiting patiently for the end.

When Armin sets out to obtain some morphium, he descends to the underworld like Orpheus, Odysseus, or Aeneas, walking through three Circles of Dante’s Inferno. The first place is a high-rise building, overcrowded with people and their frightful whispers, where he meets his friend’s distraught wife. The second place is a nightclub mirroring the moral decay of the period and the third place is a madhouse with white walls and white-dressed staff: Panoptical scenes, places which seem to exist just for themselves, submerged beyond time, just like loops of repeating actions.

The journey for morphium thus becomes a feverish delirium, a disturbingly fanciful descent into the madness of this period, which reveals that the society finds itself in the state of putrid stillness, living out the amazing orgy of its own moral demise. Armin Braun, this Kafkian convict without given cause, pursued by anonymous forces, undergoes a purging process throughout his descent, which restores his inner strength and helps him to remember the faith in a man’s ability not to act as a crooked bootlicker of the Power. The nameless life entrusted to his hands, kept safe from the pursuers, offers the light of salvation, which makes the final death come accepted willingly and without Fear.

The Dictate and Dismay

The photography by Jan Kališ is suppressing the characters magnificently, frequently leaving them somewhere in the lower-left edge of the frame and emphasizing the structure of walls and windows beside them, filming the actors through the lattice of slat, carving them out of the height of the space above and below them, leaving them to run from the echo of their own footsteps, which are too noisy and return back as the footsteps of the pursuers.

In this process of suppression, the people are transforming into structural members that finalize the scene, they move or stand still, are quiet or speak, always placed in the shot’s composition with dignity, often during the complex moves and shifts of the camera, which leaves the characters and moves elsewhere, adopts their movement and awaits their comeback, or passes in swift jumps from one character to another, prepared for its part. The camera itself divides the scenes, claiming the right to put anything aside, to give the attention to objects and make objects out of characters. Its status is truthfully privileged, it’s the source of visual richness of the otherwise intimate movie, moreover it even lets us forget about the intimacy.

The applied noises and the musical element disturb continuously throughout the film. The sounds of objects come on their own and are strangely expressive and unpleasant, be it a falling shovel, a ringing phone, a disquieting scraping of boots, a door slamming, a typewriter, a stuck gramophone disc, but also a child’s cry, an echo of voices and whispers. These and other similar noises sometimes create their own shading of the particular scene, enhance the tension of the situations. In other cases the sounds and music gain a symbolic role. For example when Braun is walking through the synagogue among the pianos at the very beginning of the movie, a piano music is playing.

Both elements (camera and sound) contribute this way to the expressivity of the film, which brings the inner experience of Armin Braun, his fear and dismay, closer to the viewer through the rawness of spaces and terror of commotions. This expressivity is enhanced by the work of Ester Krumbachová, who freed the costumes of policemen pursuing the members of the resistance and Braun himself of any signs of political affiliation or rank, which gives the danger and tyranny in the film a disturbingly anonymous appearance. It comes out of nowhere, identifies itself with no card, just with the force of its presence and confidence in its actions. The final impression that the house’s inhabitants surrender to their own fear rather than to the higher power is strangely underlined this way.

The Metamorphosis and Its Circumstances

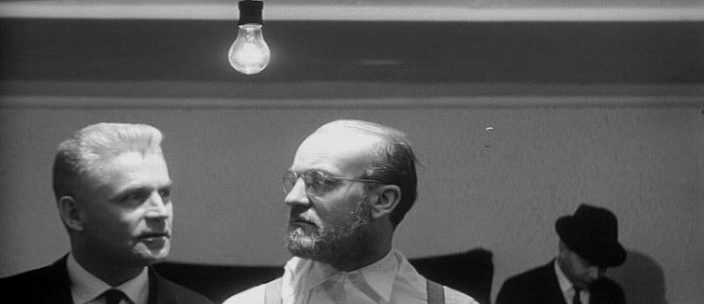

Armin Braun is portrayed by Miroslav Macháček. He shows us a lanky figure with hat and black coat, leaning on an umbrella while walking. In the synagogue it’s an old man shuffling with small, thrifty steps. He seems somewhat inappropriate in all the surrounding fuss. And he seems inappropriate even on the streets, literally running away from their exposing emptiness, bend in his waist and filled with physical unrest; a bell-ringer without the hunched back. The inappropriateness simply follows Braun wherever he goes. The dignified face and kindly voice contrast the face’s jerky movements and the roving eyes, the expressions of an ill spirit. As the film continues, however, the character straightens and the face is getting rid of that fearful panic. The shifts in physical movement, gesture, mimics and voice lead into the final lull and evened temper.

The film is pulsing at times with certain tension between its focus on the form, which subordinates the actors, and the dominant performer of the main role, who creates a fascinating complex character, achieved by the work of his whole body, his whole expression. The camera wants to integrate Macháček into its system of shots, into its plan, Macháček, on the contrary, forces the camera to base upon him, to let him play a whole scale of intricate details, which together form the character of Armin Braun.

After all the whole working process may be the very proof of that. Miroslav Macháček supposedly stated a request at the beginning of shooting for each shot to be taken only once. In the end a compromise has been reached, by filming this way unless a technical error did occur. The first shots have still been taken repeatedly anyway, but the retakes were progressively reduced and many scenes were simply made in the first run.

´

The reason for this request was Macháček’s strong belief that he can put his performance into the scene with all its intensity only if it’s not repeated. Some members of the filming crew later spoke about a unique working atmosphere, about how an unusual calm was being kept during the filming, so that Macháček, described as an eccentric actor, could focus on his performance.2

A unique position in this movie has a three-minutes-long monologue made in a single shot. Jiří Cieslar gave this scene an exceptional attention in his book Diamonds of the Everyday (Démanty všednosti, 2002). The monologue did appear neither in the original story Without Beauty, without Collar (Bez krásy, bez límce, 1962) by Hana Bělohradská, nor in the script. The long shot is the only one of its kind in the whole movie and Macháček’s performance is openly theatrical, aimed towards the camera, towards the viewers.

Because of the sound this scene was being shot in a closed set piece and the natural lighting was imitated. The camera was placed in the middle of the room and Macháček was moving along the walls. It was a technically demanding scene, because the camera followed the actor, who was constantly in motion and it turned around just as he did and even a bit more. Because of the camera’s focus, the actor couldn’t come closer to it than for one hundred and fifty centimeters. The rehearsed scene was shot twice and the film uses the second version.3 It’s a simple example, though it reveals something about the filming process nevertheless.

Macháček acknowledged following the legacy of Stanislavski. One day he found a small pocket knife, a piece of twine and two sugar lumps in the pocket of a costume prepared by Ester Krumbachová. He received an explanation that these things might help in the case of a sudden taking into a transport.4 Macháček was allegedly pleased.

The History Would Also Like to Say Something

At the beginning of German occupation in 1939, the newly established Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia had 118 310 registered Jews. Up till 1942 more than twenty thousand Jews emigrated legally, though the outset of the war had limited this option noticeably. The departure abroad was logically accompanied with the confiscations of property and many charges. Many others simply fled. In 1941 the first transports to Łódź did occur. There were five transports, each taking one thousand people, put together by the very local authorities of the Jewish religious community. One such transport was headed for Minsk. By October 21st the state of Jewish population was 88 105, with 48 000 Jews living in Prague.5 By November 24th in 1941, 342 Jewish men arrived to Terezín to prepare this fortress-town for establishing a ghetto.6

The film’s story takes place during the first wave of transports, or shortly after that. Braun does witness helplessly the systematic erasure of his own nation from the face of Prague, being even present in the process through his work. Being Jewish is a basis, which sets his position in the society, but doesn’t delimit him in any other way, Braun doesn’t even have a Jewish star stitched on his clothes. The people he lives with in the apartment house are on the contrary the telling representatives of Czech society, a reflection of the two-sided attitude of Czechs towards Jews.

There were three groups of Jews in Czechoslovakia before the war. The first ones were the not particularly popular German emigrants, the second ones were the Zionists and the third ones were Czech Jews. The Zionists went the way of asserting their own minority, while the Czech Jews wanted to integrate into the Czech society, from which they later expected protection against the power of Nazis. Before the Munich Pact, they raised for the state’s defense over 80 million out of the 480 raised in total.

The anti-Jewish mood and attitudes increased in strength here after the Munich Pact, the demands for our own national purification also gained more voice. In the case of Jewish refugees from the Sudeten, the relocation was allowed only to those who acknowledged Czechoslovakian nationality in the 1930’s census. The negative attitude towards Jews spread to the programs of political parties, some newspapers and appeared even in the pronounced statements of various professional associations. The beginning of January of 1939 brought the first anti-Jewish governmental steps and since June 21st of the same year the Nuremberg Laws came into effect.7 More than 300 restricting decrees, like the ban of selling caps or domestic animals to Jews, simply meant a complete isolation, the one step before the transports.8 Even this state is reflected in Armin Braun.

The majority of Czech nation was passive, the marginalization of Jews outside the society was even welcome by some. No bonds existed, though passive anti-Semitism did. The shot where the house’s inhabitants accompanied by the mocking stare of the police commissioner (Jiří Vršťala) pass over the dead man is a reproachful picture of Czech nation, which almost indifferently passed over the tragedy on the inside. When Braun dies, the police leaves and has no more reason to come back, the house was cleansed of the one true suspicious inhabitant, which didn’t belong among the others anyway. The Jew is dead, maybe at least the Czechs will save themselves.

And the Fifth Rider is Fear (…a pátý jezdec je Strach)

Director: Zbyněk Brynych

Script: Hana Bělohradská, Zbyněk Brynych

Photography: Jan Kališ

Cut: Miroslav Hájek

Starring: Miroslav Macháček (docent Armin Braun), Olga Scheinpflugová (music teacher), Jiří Adamíra (JUDr. Karel Veselý, owner of the house), Zdenka Procházková (Marta, Veselý’s wife), Josef Vinklář (Vlastimil Fanta, public defense commander), Ilja Prachař (butcher Šidlák), Jana Prachařová (Věra, Šidlák’s wife), Jiří Vršťala (police comissioner), Tomáš Hádl (Honzík, Veselý’s son), Eva Svobodová (housmother Kratochvílová)

Czechoslovakia, 1962, 98 min.

- LIEHM, J. Antonín: Ostře sledované filmy. Národní filmový archiv 2001, p. 161. [↩]

- CIESLAR, Jiří: Obrana samomluvy. Kapitola o filmovém monologu a herectví Miroslava Macháčka. Démanty všednosti. Pražská scéna 2002, p. 307. [↩]

- The same source, p. 319-320. [↩]

- The same source, p. 319. [↩]

- GEBHART, Jan – KUKLÍK, Jan: Velké dějiny zemí koruny české XV. b. Nakladatelství Horáček – Paseka 2007, p. 73-86. [↩]

- POLÁK, Erik: Perzekuce Židů v protektorátu v letech 1939-1941. In Akce Nisko v historii „konečného řešení židovské otázky“ k 55. výročí první hromadné deportace evropských Židů p. 181 [↩]

- KREJČOVÁ, Helena: Židé a česká společnost. Léta 1938 – 1939. In Akce Nisko v historii „konečného řešení židovské otázky“ k 55. výročí první hromadné deportace evropských Židů, p. 53-61. [↩]

- POLÁK, Erik: Perzekuce Židů v protektorátu v letech 1939-1941. In Akce Nisko v historii „konečného řešení židovské otázky“ k 55. výročí první hromadné deportace evropských Židů, p. 180. [↩]