Dita Saxová – The Girl Who Grew Up Too Fast

Původní analýza v češtině je zde. / The original analysis in the Czech language can be found here.

Introduction

Using archived sources, I will outline the circumstances surrounding the making of the film, including information on the changes in casting, the quest for the main protagonist and financial issues. I will further discuss the reviews at the time of its premiere, both in the state of Czechoslovakia and abroad. In the analysis itself, I will focus on the film style – camera and editing in particular –, and compare the portrayal of the heroine and other characters in the book and in the film.

Making of the Film

Needless to say, a whole range of aspects contribute to the final version of a film. My main focus will be on the cast, which proved to be the most problematic part of the whole film making process.

The script was originally supposed to be written by Lustig in cooperation with Jan Němec. The fee was set at 26 thousand Czechoslovak crowns, with each author receiving 13 thousand crowns. The contract was signed on 3 October 1963 and the collaborative screenplay was agreed to be handed in by 30 December 1963. However, a disagreement between the two filmmakers led to a cancellation of the contract. Years later, Lustig confided to the editor of the Czech magazine Reflex that he believed the financial aspect to be the main reason behind the termination of the co-operation with Němec. Němec wanted Lustig’s share for the screenplay.1 The literary script of the film was approved on 30 November 1966 (three versions of the literary script were created), the shooting script was approved on 16 March 1967.2

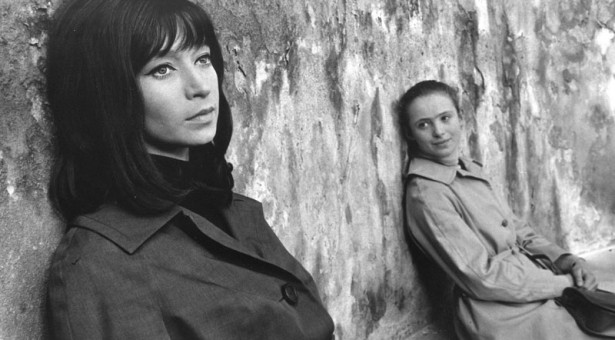

The preparations started on 11 February 1967; the filming took place from 20 July to 7 November 1967.3 Complications arose already during the quest for the perfect actress. Antonín Moskalyk was first searching for two months among the actresses in all Czech and Slovakian theatres from which he moved on to acting schools in Prague, Brno and Bratislava. From the thirty candidates Moskalyk interviewed, not one was successful. Subsequently, the director Moskalyk, together with the executive producer Vladimír Vojta and the director of photography Jaroslav Kučera, set off to Poland. From 1 to 4 February 1967, they went to see several candidates for the leading part in theatre and cinema. The list of the actresses considered included J. Jedlewska, Z. Saretoková, E. Wisniewska and A. Ciepielewska, to name a few. Neither of them nor the graduates of the theatre academy in Warsaw managed to captivate the makers of the film. Finally, they chose the actress Krystyna Mikołajewska whom they had previously seen in a theatre performance and also in the film Pharaoh. Mikołajewska accepted the part.4 For one of the supporting roles (possibly Isabelle Goldblat) the makers approached Ida Kamińska (known for The Shop on the Main Street); she, however, refused the offer.5

According to Arnošt Lustig, Antonín Moskalyk was first searching for a protagonist that would correspond to the novel’s heroine – a blue-eyed blonde. Having met the brunette Mikołajewska, he changed his decision, casting the actress by virtue of her beauty and acting skills.6

Supposedly, in one of the first versions of the cast on 6 February 1967, the lead roles were assigned to Karel Höger as professor Munk, Rudolf Hrušínský as Gottlob, Jan Kačer as Huppert and Josef Abrhám in the role of the young Swiss.7

In a letter from 17 February 1967 written by the executive producer Vojta to a Švabík’s production team we learn that Vladimír Pucholt demanded a fee of 600 crowns per one filming day for the role of Fitzi Neugeborn. A handwritten note reads: Out of the question (freely translated from the original).8

A following letter form 6 March by Vojta informs Bagarov, the casting director, about the request for transfer of Josef Abrhám into the 4th fee group (CSK 400 per one filming day) and Vladimír Pucholt into the 5th fee group (CSK 600 per one filming day). A handwritten note reads: Proposal for Abrhám’s fee adjustment approved. Proposal for actor Pucholt temporarily postponed until the term of his military service is determined. 22/3 67 (freely translated form the original).9 Minor complications concerning the fee of Blanka Waleská arose (a rise from CSK 400 to 500) and the director Moskalyk, who was awarded (together with Arnošt Lustig) for his television film a laureateship of the Klement Gottwald State Prize, moving to a higher salary range. His final fee amounted to CSK 38,000. The director of photography Jan Kučera was awarded CSK 30,900.10

By 24 March the cast was complete. It, however, underwent further changes during the filming. As we gather from the film production report: after the return from shooting on location in Tatra Mountains, further delays were caused by the illness of one of the main parts, R. Hrušínský. His role was assumed by actor K. Höger, whose role was taken by B. Záhorský. Prompt exchange of the costumes was therefore needed, together with the necessary dialogue rehearsals and preparations for filming (freely translated from the original).11 Záhorský’s former part of Goldblat was thus eventually played by Ferdinand Krůta and Höger’s former part of Munk was taken by Záhorský.

To complicate matters further, Vladimír Pucholt playing the part of Fitzi emigrated in September 1967, leaving his role to Ladislav Potměšil to be casted for.12

Moskalyk’s strive for perfection and perhaps also his inexperience in feature films might have also played its part in falling behind the schedule. The hold-up and the increased need of film material was justified by the effort to compensate for the failure of the previous Moskalyk’s feature comedy Kissing-Time Ninety.13

The initial film budget had to be increased from CSK 3 million 400 thousand to CSK 3 million 700 thousand due to the following reasons: three versions of the literary screenplay, a fastidious selection of the main protagonist, high demands on the work of the cameraman, difficulties with recreating the Swiss Alps scenery in the High Tatras as well as Moskalyk’s effort to create a valuable work of art.14 The communication difficulties caused by casting a Polish actress as the main character did not help to smooth the filmmaking either and neither did the actors leaving for holidays.15

Upon finishing the work, a three-week delay was created due to the absence of three candidates (Jiřina Jirásková, Blanka Bohdanová and Eva Klepáčová – Blanka Bohdanová was chosen at the end) for the postproduction sound of the main protagonist from the state of Czechoslovakia.16 The film premiered on time despite the complications, opening 23 February 1968.

Period Reception

Because there were only a handful of reviews and references in the foreign press, one cannot infer whether the film was perceived more positively abroad than in Czechoslovakia or what criticism was addressed to the film. The corpus of reviews and criticisms in the Czechoslovakian periodicals was, on the other hand, so wide ranging that no definite conclusions can be drawn.

The contemporary critiques and reviews often criticise the adaptation style and the portrayal of the main protagonist. Time and time again do they observe that the awarded Prayer for Katerina Horovitzova was a much more successful literary adaptation. In the next section are the most stimulating passages from the critical reviews and critiques, a few of them, such as Kulturní noviny (Culture News) and Mladá fronta (Young Front), elaborate on the film quite substantially.

Specialised Press

The magazine Kino (Cinema) featured a Gustav Francl’s critique called Otazník nad Ditou Saxovou (Obscurity surrounding Dita Saxová). The author pondered on the form of the film version, which, according to Francl, was theatrical, yet Moskalyk failed to tailor the topic to the film version, nor did he curtail the plot down to the fundamental dramatic encounter. To the contrary, he shot quite a wide-range of material while only showing bits and pieces. Francl believes the protagonist as well as the whole film to be missing their background: she is reminiscent of a character meticulously and artfully extracted from the spinning fibre of the time and era. Involuntarily she becomes an oddity we can’t quite sympathize with . . . I could not but feel that everything she is going through is just a game and she acts in an incomprehensible heat of passion (freely translated from the original).17 Francl observes that the acting bears the marks of a tottering adaptation and only appreciates the beautiful camerawork of Jaroslav Kučera.18

Lída Grossová proposes an interesting point of view in the newspaper Kulturní noviny (Culture News), comparing the character of Dita in Lustig’s novella (she characterizes it in quite a detail) and in the film. Moskalyk read Dita affectively but his adaptation failed to show it. The choice of a Polish actress Krystyna Mikołajewska entails a stunning, finely modelled Dita so aristocratic that her delicacy and her emotional depth can barely be spotted beneath the perfectly mastered gestures, noble speech and on her beautiful yet motionless face (freely translated from the original).19 Grossová goes on to write that Moskalyk does not evoke with one word or picture the horrors Dita had to undergo and survive. The closest to it being a short digression to a sweet idyll from Dita’s childhood. A viewer ignorant of the novella cannot, as Grossová believes, understand the film version of Dita.20

The newspaper Filmové a televizní noviny (Film and Television News) featured a critical analysis by Drahomíra Novotná claiming that Moskalyk does not seem to be a filmmaker capable of detecting weak spots in a screenplay. She further adds that the expressive pictures are shallow; ideas vanish the moment they are pronounced. The skilfully constructed scenes fail to unify the form with the content . . . I find the fundamental error to be in the screenplay. It contains too many proclamations conveyed with the use of expressive dialogues and lacks – especially towards the end – a strong narrative thread . . . (freely translated from the original). 21

Daily Newspaper

Rudé právo (Red Rule) featured a review with an apt headline Dita Saxová – s rozpaky i výhradami (Dita Saxová – abashed with reservations), where the author meditates on the problematic aspects of the film and speculates primarily about casting of the main character. The main issue he finds is the excessively sculpturesque and cold appearance of the Polish actress and prolonged settling of the camera on her physique. This method makes Dita only physically exceptional, leaving the viewer out in the cold, obstructed from her inner drama. Other characters are equally left in a certain vacuum; believability of the story and setting is missing.22

Eva Vacíková wrote in the journal Večerní Praha (Evening Prague) that the film version was missing the portrayal of the warm environment represented by the caretaker Goldblat and his wife. Another issue she found with the film was the protagonist, observing that different casting would have made all the difference. Where Lustig’s word carves Dita’s complex personality, an actress roaming the film resembles a beautiful mannequin; the camera rests lengthily on her photogenic beauty, making her a creature static on the outside as well as on the inside . . . (freely translated from the original).23

The journal Mladá fronta (Young Front) published Svatoslav Svoboda’s thought-provoking article called Paradoxy přepisu (Paradoxes of Adaptation) which studies the shift between the characters in film and the novel. However, Dita is not the only character he discusses. Fitzi is seen as a character similar to the tragic characters from the film Diamonds of the Night. While Brynych’s Transport from Paradise and Němec’s Diamonds of the Night ventured to a much more distinctive adaptation with astonishing results, Moskalyk took the novella with too great of a consideration.24

Alois Humplík in the journal Práce (Work) points out that the film version of Dita . . . comes across as a slightly eccentric creature whose confusion we cannot grasp no matter how hard we try. . . The adaptation bares merely traces of incomprehensible allusions, clues and symbols (freely translated from the original).25

Vlastimil Vrabec in the journal Svobodné slovo (Free Word) criticises the choice of the actress, arguing that a deeper insight into the psyche of the main character is beyond Mikołajewska’s strength. He also questions the reasons behind her casting, arguing that finding a Czechoslovak actress would have been a better and also an achievable choice.26

Karel Holý is one of the few without any reservations. Quite the opposite, really. He praises the film in the journal Pravda (The Truth), including Mikołajewska’s performance, who he believes acts with all of her personality, willowy fingers, sorrowful face, physical beauty and, above all, her heart (translated freely from the original).27

Václav Šašek assesses the film positively in the journal Zemědělské noviny (Agricultural News) and mentions only slight reservations: There are, however, several errors casting a pall over the film, especially in the first third. These are probably errors already within the script: literary dialogue, too obvious an effort to differentiate Dita from the other characters from the very beginning, portraying her more profound and wise, leaving us too close to loathing her for her using every chance to utter a speech full of wisdom, to name one (freely translated from the original).28

Reaction Abroad

The 14th San Sebastian International Film Festival rated Dita Saxová one of the most popular films. It received a National Film Society Award and also a special Jury Award – a Silver Seashell (together with a Hungarian film Summer on the Hill by Péter Bacsó).

The Spanish newspaper ABC was of the opinion that Dita Saxová represents a reflective film, a logic where nothing is left untouched or free for improvisation; every gesture stems from an apt goal and forms a component yet cold pictorial beauty (freely translated from the original).29 The camera work, direction, screenplay and the performance are all appraised. Mikołajewska is perceived as convincing.

The French Cahiers du Cinéma mentions that the film was originally to be directed by Michelangelo Antonioni who failed to agree on the financial conditions.30 Further we read that it is a highly alluring film, momentous, theatrical and delicate in itself, . . . weighing down towards aestheticism or formal conformance (freely translated from the original).31 Criticised is the glossy eroticism, the sequence in Switzerland and the symbolic suicide.

Analysis

In this chapter I will compare selected aspects of the novella and the film, primarily the portrayal of the main protagonist and the supporting roles and their relationships. I will also focus on the style analysis of the film, taking into account the statistical analysis.

Selected Aspects of the Novella and the Film

The novella Dita Saxová was first published in 1962, subsequently released in a number of further editions and translated into several languages. Lustig rewrote the book after the first publications, which might have been caused by his work on the screenplay and the film version itself. An extended edition of Dita Saxová was published in 1997. A comparison of the gradual changes of Lustig’s versions of the novella deserves a separate analysis. I will only concentrate on a few aspects of the work.

As palpable from the contemporary reviews, the character of Dita in the film version was perceived as highly problematic. Let us first look at her with the eyes of the author himself, who was inspired by a real-life girl: She was a beautiful eighteen-year-old girl whom we all in the Old Town of Prague knew, admired and befriended. A tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed Jewish girl, very beautiful, she looked grown-up. She survived three years of war, was not raped and returned from the camp unimpaired. She would smile as girls sometimes do with a mysterious and promising smile, which made us believe she was happy. In reality she lost both of her parents, her uncle and her friends. She survived fatigued, but refused to show it. Peace did not provide her with what she expected. And one day she killed herself (freely translated from the original).32

The whole novella is built on this contrast and Lustig wished to preserve it in the film, but the director chose a different direction in the end: [Moskalyk] was of the opinion that every Jewish girl needs to be black-haired, brown-eyed and melancholic. If you ask me, the girl should have been merry and full of life the whole film through and then jump of the cliff – and the viewer would be completing the film in their mind on their way home. But Moskalyk did not trust the viewers, so Dita is sad and stereotypical and has to walk in dancing shoes in the snow which she is not pleased with (freely translated from the original).33

Lustig described the difference between the novella and the film in the following terms: The film version of Dita is sad from the very first moment and dies equally sad. In the book she attempts to hide her sadness and not trouble the others. The novella version raises the question why and the film version answers it (freely translated from the original).34

The story is situated mainly in Prague, 1947. The novella is written in third-person narration; told by an omniscient narrator who reveals to us the inner incentives and thoughts of the main character. This was not achieved by the film creators who, by opting for a substantially aestheticizing elements, prevented us from at least partially “linking” to the protagonist’s feelings and thus resigned on the attempt to mediate the Holocaust experience.

The retrospective scenes lacking visualisations of the Holocaust might be considered problematic in this sense. We may ask how would the inclusion of the retrospective scenes change the final impression of the film, if we were shown, for example, what is described in the novel: In the autumn of 1944 she had stood before a soldier who was supervising the distribution of underwear. He wore polished leather riding boots and green leather vest. With a jerk of his thumb he motioned for her mother to move on. Dita knelt in front of him and begged him to reconsider. He had hollow eyes and all the power in the world. He kicked her. She was almost glad when she fell, face down in the mud.35 It is evident that the film, composed as it is, has no space for such scenes as they would stand out completely. Moskalyk’s film is truly an aesthetic piece of work and ugliness does not make the cut (Dita’s death is also aestheticized). Showing allusively – some scenes could have surely been incorporated that would evoke “at least” the atmosphere of fear without necessarily showing the concentration camp – what Dita was going through is what the filmmakers could have gone for but chose not to.

Instead of the quotation above, the film features an altered Dita’s narration. Her friend Tonitschka’s declaration (see video) – You are like my mother – induces Dita’s reminiscence of her as a little girl running from an underpass and joining her parents walking on a street. Simultaneously, she describes to Tonitschka the harsh memory the word “mother” evoked in her. We were being sorted by an elegant German doctor. He sent my mother the wrong direction. . . and let me live. I kneeled in front of him in the mud and begged him. He let me kneel. . . and mother went without saying a word (freely translated from the original). The following scene where Dita consoles Tonitschka reveals her own incertitude and concern (not only) about Tonitschka’s life.

The opening titles offer a long shot of a young girl we deduce to be Dita at a young age, which proves to be true in the first retrospective.36 Here we watch Dita playing in the backyard. In the second retrospective she joins her parents and walks with them on the street (see above). Another retrospective shows her playing with a ball and throwing it to her father (she remembers him saying: Father never had another woman. . .). In her last memory before death, Dita is called in by her mother for lunch and then sits at the table with her parents. Symbolically she once again meets her parents who died at the concentration camp.

As an audience, we can see only Dita’s idyllic childhood, her memories of her parents. The tragedy we mostly infer. It feels like the filmmakers counted too much on the presumed familiarity with the novella that was being read plenteously then and did not consider it necessary to clarify or remind us of some context and plot.

Dita’s death is one of the best made scenes in the context of the film. We finally see the portrayal of Dita’s mental state in her physical appearance, when in a brief, detailed shot (approximately 4 seconds long) we can study the face of the protagonist, not so faultless as opposed to the rest of the film, she has ruffled hair and appears genuinely broken.

The novella puts an emphasis on the contrast between the innocence and the experience, resulting from her internment at the concentration camp. As mentioned above, the filmmakers attempted to portray this contrast primarily with external, visual means, with the protagonist’s speech and facial expressions, and, needless to say, with the help of camerawork. The novella here offers clues (D.E. managed to look at her now . . . She lifted the corners of her lips, as if she were smiling to herself without opening her mouth.37 She rewarded him with her grown-up smile.38)

Dita’s frequent fixed stare straight forward both when alone and when she communicates with others also feels unnatural. The dialogues where the protagonist is placed in the foreground and the second person in the background (or they are both in the same plane, looking at each other, but the second has a fixed stare) are nothing new in filmmaking. They are often used for a dramatic effect and are logically connected with the content of the dialogue. This film, however, overuses this method. Dita thus becomes rather dehumanised, with emotions which she barely shows on the outside, forcing the viewer to search for them.

Dita’s dehumanisation and sadness are not unmotivated. It is apparent that she does not find what she wants in her life. If we were to look at Dita’s relationship with other characters, we are safe to proclaim men a disappointment – she fails to find support in them (superficial David Huppert, slick Gottlob, and inexperienced Fitzi). Gradually she loses her friends – Liza gets married, and Britta leaves for England. Her only true friend is Tonitschka, whom she dotes on. After her loss, Dita only exists to consequently take her own life. The search did not bring her happiness.

In the novella we find Dita’s favourite saying several times: Life is not what we want but what we have. In the context of the novel, it does not feel contrived, but because of the film’s almost minimalistic interpretation, Dita’s quotations as performed by Krystyna Mikołajewska are but empty words, to which adds the monotonous recitation.39

There are no major deviations from the novella in the depiction of the main characters. There are, however, several fundamental differences in the portrayal of the relationships between the characters and in the order of the scenes. Isabelle, the caretaker Goldblat and his wife become somewhat third-class characters in the film. The film accentuates more the relationship between Tonitschka and Dita. This mutual dependence (Tonitschka admires Dita, Dita has a close attachment to her, helps her as if she were her older sister) is emphasised by the fact that – as opposed to the novella – Tonitschka dies in the film and Dita’s feelings of guilt are amplified by the fact that she was not with Tonitschka at her worst. Instead, she agreed to spend the evening at the bar with Gottlob. The sequence with Gottlob, which remains mostly unaltered, only with necessary cuts, is therefore intentionally placed before Tonitschka’s death. This choice stands in contrast with the novella where Dita and Gottlob meet before his wedding with her friend Liza Vagner. This proves to be one of the successful moves of the filmmakers who go on to show Dita walking to the Prague district of Hradčany where, together with Tonitschka, she spends moments of happiness in intimate conversation. While Dita changes almost imperceptibly, the motivation for one visible change is precisely Tonitschka’s death, for which Dita blames herself.

Without having read the novel, the audience is left outside of several relationships between the characters (Gottlob – Huppert; the ideological opposition of Munk – Gottlob is not accentuated as much as in the book, but the viewer realises quite quickly that Gottlob represents the bourgeois pole while Munk strives to fulfil socialist ideologies). The viewers nowadays might not be able to catch all the hints and clues that the contemporary audience understood with ease. For instance, the abbreviation R.U. that Linda Huppert writes on the train signifies “Rückkehr unerwünscht”, which translates as “return undesirable”. This sign was used to indicate the carriages that were headed to the concentration camps.

Style Analysis

The film Dita Saxová was shot on a black and white widescreen material, the cameraman was Jaroslav Kučera, who had experience from the films Diamonds of the Night, Pilgrimage to the Virgin Mary, Daisies, When the Cat Comes etc. Zdeněk Stehlík was the editor of the film. He participated in the film Nobody Will Laugh, The White Lady, Here in Mechov, The Fabulous World of Jules Verne and many others. He collaborated with Moskalyk on his previous endeavour already mentioned – Kissing-Time Ninety. Camerawork and editing together with the soundtrack are a true pride of the film.

A great emphasis is put on the work with period costumes, mise-en-scene and the colour tuning – using the usual black-and-white in some scenes whilst adding filters to the rest. Widescreen format is used mostly in positioning individual characters at the edges of the shot (Dita and Huppert) and in composing shots with great width of sharpness (which is used, for example, in the sequence of Tonitschka’s death, where we see Dita walking through the corridor). Another factor craft fully handled is the framing (e.g. in the scene of Tonischka’s death or of the dialogue between Dita and Herbert Lagus).

The film captures our attention with its long scenes that are more demanding on the actors. The longest shot in the film is 2 minutes and 21 seconds long. It is the sequence where Dita sits at the bar at a table with Gottlob. The camera slowly approaches the two while, simultaneously, Gottlob approaches Dita both with his physical presence and his flatteries and intimations. One of the longest sequences (116 seconds long) appears in the scene where the doctor examines Dita.

The scene with the celebration (Dita’s performance) and the subsequent scene with the girls dancing and the arrival of Munk ranks among the most interestingly approached long sequences as to the camerawork. We are watching Dita’s graceful movement while the camera circles around her. The most striking element of this scene is the amazing music by the composer Luboš Fišara, whose piece of work makes this scene truly unforgettable. Noticeable is also the work with foreground and background. The viewer might notice how Dita’s dance evokes reactions of her friends Liza and Britta (bored, perhaps jealous) and Tonitschka (admiringly staring at her) in the background.

The shortest shot in the film Dita Saxová is 2.2 seconds long. The average length of a shot (not counting the opening titles) is 21.9 seconds. The total number of shots is 276.40 In the closing part of the film, in the room of the Swiss villa we witness an interesting “staring contest” featuring two brothers and Dita. We can watch the gazes of individual protagonists (in the context of the film) in short shots (ca. 15 seconds long) which capture in medium shot every single participant (see video) – Dita stares at the clock, one brother watches Dita and the other watches both Dita and his brother.

For comparison: in the film Diamonds of the Night (1964) the average shot length is 7.8 seconds with the longest shot being 142 seconds and the shortest 0.8 seconds long. The total amount of shots is 488.41 Transport from Paradise (1962) counts (excluding the closing credits) 262 shots, the longest one reaching 110.8 seconds and the shortest one 0.7 seconds. The average shot length is 20.4 seconds.42 The Fifth Horseman is Fear (1964) totals (excluding opening titles) 307 shots with the longest one lasting 169 seconds and the shortest one 0.9 seconds. The average shot length is 18 seconds.43

Conclusion

Antonín Moskalyk aimed, to use his words, to remind people of how this fragile creature [Dita Saxová], who lived the most beautiful years of her youth in fear and on the verge of death, has come back to life. . . . She expected warmth and love. Because she was lacking that before. But life gave her a different welcome. . . (freely translated from the original).44 Moskalyk succeeded in capturing Dita’s emptiness. Sadly, he did not manage, for various reasons, to shoot a film equally powerful as, for example, The Fifth Horseman is Fear, Diamonds of the Night or Prayer for Katerina Horovitzova. We may consider the main cause to be the casting of the main character, an insufficient evocation of Dita’s past etc. The key role in acceptance or rejection of the film plays the main character – whether we agree with her representation of the role. The film is, nonetheless, a delight as far as the visuals and soundtrack are concerned.

Dita Saxová

Directed by: Antonín Moskalyk

Screenplay by: Arnošt Lustig, Antonín Moskalyk

Director of Photography: Jaroslav Kučera

Edited by: Zdeněk Stehlík

Soundtrack: Luboš Fišer

Cast: Krystyna Mikołajewska (Dita Saxová), Bohdanová Blanka [dab] (Dita’s voice), Bohuš Záhorský (professor Munk), Karel Höger (advocate Gottlob), Martin Růžek (MUDr. Fitz), Noemi Sixtová (Tonitschka Blauova), Klepáčová Eva [dab] (Tonitschka’s voice), Jaroslava Obermaierová (Liza Vagner), Yvonne Přenosilová (Britta Mannesheim), Dana Syslová (Linda Huppert), Josef Abrhám (David Egon Huppert, Linda’s step brother), Ladislav Potměšil (Alfred Neugeborn called Fitzi), Jiří Menzel (Herbert Lagus), Pavel Kollmann (Mr Werli), Nelly Gaierová (Mrs Werli), Jaromír Petřík (older son Werli), Friedl Milan [dab] (older son’s voice), Zbyněk Pohlídal (younger son Werli), Kodet Jiří [dab] (young son’s voice), Ferdinand Krůta (caretaker Goldblat), Blanka Waleská (caretaker’s wife Isabelle) and others

103 minutes, 1967, Czechoslovakia

Premiere: 23 February 1968

References

LUSTIG, Arnošt. Dita Saxová. Praha 1962.

LUSTIG, Arnošt. Interview. Vybrané rozhovory 1979-2002. Praha 2002.

KADLECOVÁ, Kateřina. Láska je příšerná slabost. Reflex nr. 25, 2009.

Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. Film Dita Saxová. Lustig, Arnošt – Moskalyk, Antonín. Literary script. October 1966.

Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Lustig, Arnošt – Moskalyk, Antonín. Literary script. January 1967.

Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Moskalyk, Antonín. Shooting script. March 1967.

Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets.

Bibliography

Český hraný film IV. 1961-1970. Praha 2004.

Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1968, nr. 11-12, p. 21-23.

dn [Drahomíra Novotná]. FTN 2, 1968, nr. 4, p. 2.

FRANCL, Gustav. Otazník nad Ditou Saxovou. Kino 23, 1968, nr. 5, p. 7.

GROSSOVÁ, Lída. Dita Saxová. Kulturní noviny 1968, nr. 11, p. 6.

HUMPLÍK, Alois. Dita Saxová na širokém plátně. Práce 24, 22. 2. 1968, nr. 52, p. 7.

HOLÝ, Karel. Dita Saxová. Pravda 49, 22. 2. 1968, nr. 45, p. 4.

HOŘEJŠÍ, Jan. Dita Saxová – s rozpaky i výhradami. Rudé právo 48, 7. 3. 1968, nr. 66, p. 5.

SVOBODA, Svatopluk. Paradoxy přepisu. Mladá fronta 24, 29. 2. 1968, nr. 59, p. 2.

VACÍKOVÁ, Eva. Dita Saxová. Večerní Praha 14, 21. 2. 1968, nr. 44, p. 3.

vbc [Vlastimil Vrabec]. Filmový příběh Dity Saxové. Svobodné slovo 24, 23. 2. 1968, nr. 53, p. 6.

[Václav Šašek]. Premiéry našich kin. Dita Saxová. Zemědělské noviny 24, 15. 2. 1968, nr. 39, p. 2.

Online Sources

…a pátý jezdec je strach <http://www.cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3096>

accessed 25 November 2010

Démanty noci <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3124>

accessed 25 November 2010

Dita Saxová <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3095>

accessed 25 November 2010

Transport z ráje <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3129>

accessed 25 November 2010

Skutečná Dita Saxová byla sexbomba <http://uud.zcu.cz/akce2008.php>

accessed 25 November 2010

Audiovisual Sources

DVD Dita Saxová. Bonton Film 2007.

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheet of Dita Saxová, nr. 16063. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Travel report on abroad journey. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Travel report on abroad journey. [↩]

- DVD Dita Saxová. Bonton Film 2007. Interviews: Arnošt Lustig. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Film production report, unpaged. [↩]

- Pucholt’s emigration was thoroughly discussed in the press. The first impulse was initiated by the director Jiří Krejčík, whose letter (from 26 September 1967) elucidating Pucholt’s reasons for leaving to the USA held the name of “Proč odešel Vladimír Pucholt?“ (What made Vladimír Pucholt leave?) and was reprinted by the journal Práce (Work) on 30 March 1968. Further periodicals published articles most often called “Případ Pucholt” (The Pucholt Case). [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Production sheets. Proposal for the Barrandov Film Studio director meeting. [↩]

- FRANCL, Gustav. Otazník nad Ditou Saxovou. Kino 23, 1968, nr. 5, p. 7 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- GROSSOVÁ, Lída. Dita Saxová. Kulturní noviny 1968, nr. 11, p. 6. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- dn [Drahomíra Novotná]. FTN 2, 1968, nr. 4, p. 2. [↩]

- HOŘEJŠÍ, Jan. Dita Saxová – s rozpaky i výhradami. Rudé právo 48, 7. 3. 1968, nr. 66, p. 5. [↩]

- VACÍKOVÁ, Eva. Dita Saxová. Večerní Praha 14, 21. 2. 1968, nr. 44, p. 3. [↩]

- SVOBODA, Svatopluk. Paradoxy přepisu. Mladá fronta 24, 29. 2. 1968, nr. 59, p. 2. [↩]

- HUMPLÍK, Alois. Dita Saxová na širokém plátně. Práce 24, 22. 2. 1968, nr. 52, p. 7. [↩]

- vbc [Vlastimil Vrabec]. Filmový příběh Dity Saxové. Svobodné slovo 24, 23. 2. 1968, nr. 53, p. 6 [↩]

- HOLÝ, Karel. Dita Saxová. Pravda 49, 22. 2. 1968, nr. 45, p. 4. [↩]

- [Václav Šašek]. Premiéry našich kin. Dita Saxová. Zemědělské noviny 24, 15. 2. 1968, nr. 39, p. 2. [↩]

- Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1968, nr. 11-12, p. 21-22. [↩]

- For another reference to Antonioni see: Skutečná Dita Saxová byla sexbomba <http://uud.zcu.cz/akce2008.php> accessed 25 November 2010 [↩]

- Československá kinematografie ve světle zahraničního tisku 1968, nr. 11-12, p. 23. [↩]

- LUSTIG, Arnošt. Interview. Vybrané rozhovory 1979-2002. Praha 2002, p. 169. [↩]

- KADLECOVÁ, Kateřina. Láska je příšerná slabost. Reflex nr. 25, 2009, p. 58.

Dita Saxová is a blonde in the literary script from January 1967: A kdybych měla černé vlasy, jako třeba ty, a nebyla tak krásně skandinávsky plavá, slyšela bych asi méně, než mohu slyšet takhle (s. 3) (can be translated as: And if I had black hair, like you do, and was not so beautifully Scandinavian blonde, I would probably hear this less.) [↩]

- LUSTIG, Arnošt. Interview. Vybrané rozhovory 1979-2002. Praha 2002, nr. 171. [↩]

- LUSTIG, Arnošt. Dita Saxová. Evanston, Illinois 1993, p. 32. [↩]

- In the shooting script from March 1967 the opening titles are approached in a different manner. Instead of a static shot of young Dita, we are shown a sequence depicting the relationships between two characters, namely the bashful relationship of Munk and Dita. Other characters, including Goldblat, Linda Huppert and Liza Vagner, are in the surrounding windows. The film uses a part of the former sequence after the opening title, showing the girls in the windows. [↩]

- LUSTIG, Arnošt. Dita Saxová. Illinois 1993, p. 123. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 167 [↩]

- Mikołajewska was dabbed by Blanka Bohdanová. In my opinion she did a good job. Mikołajewska evidently speaks Czech in the film, which makes a good impression – the detectable deviations are minimal. Tonitshcka was played by Noemi Sixtova, who was dubbed by Eva Klepáčková. [↩]

- Dita Saxová <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3095> accessed 25 November 2010. [↩]

- Diamonds of the Night <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3124> accessed 25 November 2010. [↩]

- Transport from Paradise <http://cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3129> accessed 25 November 2010. [↩]

- The Fifth Horseman is Fear <http://www.cinemetrics.lv/movie.php?movie_ID=3096> accessed 25 November 2010. [↩]

- Barrandov Studio a.s., archive, collection. Screenplays and production documents. Film Dita Saxová. Lustig, Arnošt – Moskalyk, Antonín. Literary script. January 1967, p. 1. [↩]