On Fuller’s war experience in Bohemia

As already mentioned in the introductory profile article of Samuel Fuller (see part 1 here), this Hollywood screenwriter, who has only later become himself a film director, participated actively as an infantryman in the World War II. By the end of his war-journey across Europe, he found himself with his division in the western Czech town of Sokolov (back then called Falkenau) where he memorably recorded on film the liberation of the local prison camp. A mini exhibition commemorating his heritage was opened in a museum in Sokolov last year, vividly describing and clarifying his “Sokolov experience”, which we highly recommend for visitation.

Here we made an interview with the director of the museum, Michael Rund, on Fuller’s visit of Sokolov.

In the autobiography A Third Face which Samuel Fuller wrote and dictated in his declining years and which was published posthumously, the prison camp is inaccurately referred to as a concentration camp. Could you correct this little personal mistake of Fuller’s?

There were Czechoslovak army barracks built in Sokolov during the First Czechoslovak Republic and during the years of 1941-45 there was a military hospital of Nazi prison camp Stalag XIII B, located in the barracks with the headquarters in Wieden. Due to bad living conditions, 2200 people, mostly from former Soviet Union, died here. Somewhat altered camp (with gas chambers and crematoriums that actually never were present in the camp) also appeared in a film dedicated to the First Infantry Division called The Big Red One from 1980 starring Lee Marvin.

The whole of Samuel Fuller’s stay in the area of today’s Karlovy Vary region has not been fully mapped yet. Only piecemeal information exists at this moment. But we can mention two interesting moments connected to this place that are described in Fuller’s autobiography, published under a title A Third Face. On page 217, Fuller describes how an American soldier takes a female prisoner that has fainted into his arms and carries her to the infirmary. Fuller also modified this episode and used it in his war film, The Big Red One. In this modified version the soldier carries a child instead of a woman. Reading the unpublished manuscript Osvobození Sokolovska americkou armádou 1945 (translators note: could be translated as The Liberation of the Sokolov Region by American Army 1945) from the year 1995 written by Václav Němec, we were surprised to find this never published memory of Polish prisoner Czeslawa Malinowska, that thinks back to the liberation of the Svatava concentration camp for women on 7 May 1945:

“Afternoon May 7, just when we were being given a soup, someone shouted: Tanks! Americans! We raised from the floor heedless of the soup being spilled, and ran out of the block. Out ran also the French women and girls from other quarters. The French were singing Marseillaise. The guards were standing still at the headquarters. We couldn’t even speak with all the joy. The Americans took great care of us. They assembled us at the roll-call place in order to count us. The Germans managed to destroy all our identifications in time. One prisoner fainted during the roll-call. An American soldier took her into his arms and carried her to the district. Other brought a can and a cooker, heated the soup and poured it carefully into the girl’s mouth.”

It is mentioned in the 16th Regiment report that Fuller’s superior captain Richmond had driven to the Svatava concentration camp, so it is therefore supposable that Fuller was there as well.

Another interesting moment is described in Fuller’s book in a scene on page 221, where Fuller states: “There was a little bridge over a stream behind some barracks. We approached the bridge and found ourselves nose to nose with group of Russian infantry.” This bridge can’t be any other but the bridge called ‘Chebský most’, connecting the town of Karlovy Vary and its part Rybáře. There was a checkpoint P 659930 set up there in May 1945 and the soldiers from the 16th Regiment that Samuel Fuller was a member of were among those who were on guard there.

An interesting observation made by Fuller is that the first few contacts with Russian front-line soldiers, that were, like the Americans, hairy and dirty, were friendly. They would embrace and kiss. The Russians would give vodka to the Americans and the Americans would hand out Mickey Mouse watches in return. The atmosphere was very friendly the whole time. Six days later there was an exchange and new soldiers arrived directly from Moscow in perfectly fitting uniforms. These soldiers were not on speaking terms and the mood fell to its lowest ebb. Fuller considered it to be a “Cold War” cloud.

Have you been contacted by anyone from the range of historians addressing themselves to the Samuel Fuller work in the terms of specification of the information about his “Sokolov experience”?

Last year we communicated with film historian Marsha Orgeron from the USA who was analysing Fuller’s shots in the contribution, called “LIBERATING IMAGES? Samuel Fuller’s Film of Falkenau Concentration Camp”.1 We were correcting some mistakes in the already published article.

When exactly did the idea to dedicate one of the permanent exhibitions of the Sokolov Museum to Samuel Fuller emerge?

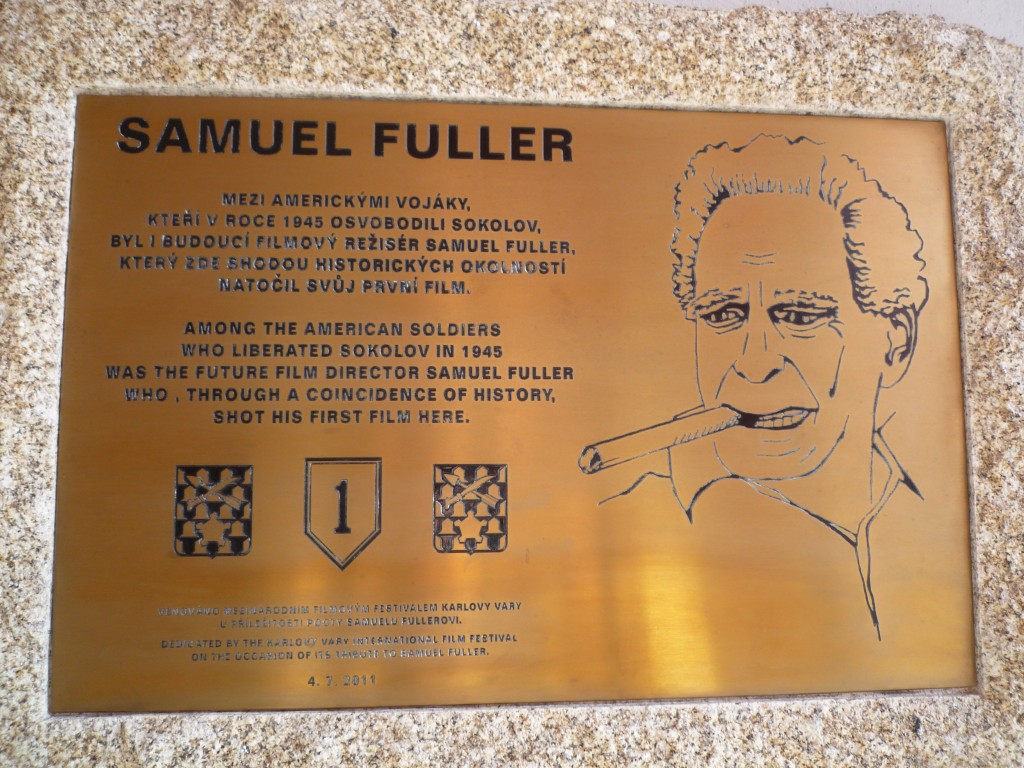

Mr Mucha, the executive director of Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, turned to us in spring 2011 and outlined that within the 46th International Film Festival in 2011 there will be one section dedicated to the so called Tribute to Samuel Fuller. The festival initiated and financed the placing and unveiling of the plaque which commemorated the soldiers from the 16th Regiment, First Infantry Division and namely Samuel Fuller. Due to the date of the festival, the most suitable date for unveiling the plaque turned out to be 4 June 2011, when the United States celebrate Independence Day.

The unveiling of the plaque dedicated to Samuel Fuller was accompanied by an activity suggested by PhDr. Vladimír Bružeňák, a professor of a local grammar school and a historian. The activity was financed by the town of Sokolov. There was a three language information board built (CZ-EN-RU) close to the memorial of the Soviet captives at the place of the mass graves, next to the Sokolov cemetery. At the place of the former infirmary, there was a memorial stone put with an inscription reminding us of the prison infirmary.

Have there been any visitors who visited the Sokolov museum just because of Fuller? If so, how big group do they form?

Samuel Fuller is known rather among the foreigners and here in Bohemia among the movie gourmets and history lovers. And these are heading to Sokolov because of him. Lately, our museum is more and more frequently visited by the descendants of the Soviet captives, who want to visit the place of their ancestors’ last sleep and learn as much as possible. Not many people know that only a few years ago the military archives in Russia were declassified. The descendants then don’t hesitate to drive thousands of kilometres and the encounters are always very moving.

As a part of the exhibition, there are also unique shots that Fuller filmed on his 16 mm camera in Sokolov in spring 1945 and later he also put them to good use in his documentary Falkenau: The Impossible from 1988 revived by Emil Weiss. How do you judge their significance from the historical point of view?

We can look at the shots from two points of view. I am not able to judge the first one objectively, but from my lay point of view I assume that “germs” of Fuller’s later film mastery can be found in the shots. What I mean by this are for instance different details in the film, for example the shots of moving vehicles, where Fuller filmed only details of wheels and belts instead of the whole vehicle, or when he didn’t hesitate and filmed directly among the men pushing a hearse up a steep hill near the Sokolov hospital. The ending of the film is also interesting. The camera focuses on the shades of men standing above the mass graves. And those are only examples.

From the historical point of view, taking into consideration the regional point of view, it is a unique documentary showing events that would otherwise be forgotten. Besides other things it is for example also interesting that in Falkenau (today’s Sokolov), together with the Americans, the Soviet soldiers had “their” prison infirmary under control already on 9 May 1945. How they appeared here so fast is a little mystery because to the near town of Karlovy Vary the Soviet army arrived on May 11 (see for example http://www.fofifo.com/strana4.htm).

From the international point of view we are dealing with very interesting shots that are unique also because they were not filmed by an official cameraman, but by an “ordinary” soldier. It is very well documented here in what way the Nazis treated the “submen” that they considered the Soviet soldiers to be, and who, when not being able to work anymore in one of thousands working commandos in the area of Saxony and Bavaria, were placed to an “infirmary” and here they usually died of tuberculosis or from general bad nutrition. By the end of the war there was no medication available and the food supply was minimal. Details can be found for example on this website. Therefore, even if is not a footage connected to holocaust as it is sometimes mentioned, it is very important that it is preserved.

On the occasion of Fuller’s miniretrospection last year at the festival in the nearby town of Karlovy Vary, his wife Christa, together with their daughter Samantha, and granddaughter Samira visited the town of Sokolov. How did they perceive the atmosphere of the town that their husband, or rather father and grandfather, together with American soldiers liberated decades before?

The whole encounter was very moving. The more so because our friend and military history lover Petr Duda arrived with his son for the celebration in historical American military uniforms with the First Infantry Regiment insignias on the shoulder, the same uniforms that Sam Fuller wore. You can soak up the atmosphere for example here. Just as a matter of interest, a cult film director Monte Hellman who participated in the filming of The Big Red One (as a director of the second film crew, editor’s comment) also visited the town of Sokolov.

It is written on your website that you are preparing a separate publication (and an exhibition) about the prison camp in Sokolov. At what stage are these preparations and how big space in the publication will be devoted to Sam Fuller?

We have already written about Samuel Fuller in our museum publication Ve spárech orlice (translators note: could be translated as In the Eagle’s Talons) about the Sokolov region during the years 1938-1945. This is unfortunately already sold out. For the next year we are preparing a book about the liberation of a major part of the Karlovy Vary region by the Americans in spring 1945. Here, Sam Fuller will naturally have his place. Further ahead we would also like to publish more publications, among other things also about the prison camp. The films made by Fuller will surely be mentioned there. It is all nevertheless a long term issue and many materials need to be examined.

Thank you for the interview

Jana Bébarová